Biology

WKU Geomorphology students learn about landscape processes in the Ozarks

- Thursday, March 28th, 2013

A group of WKU geography and geology students braved snowy weather at the beginning of March to participate in a field trip to the Ozarks, including the Salem Plateau and the St. Francois Mountain area of southeastern Missouri as part of a Spring 2013 course in Geomorphology taught by Dr. Jason Polk.

Hoffman Institute staff member Benjamin Miller (second from left) explains how the Elephant Rocks formed millions of years ago to WKU students (from left) Michelle Foley, Adam Aldridge, Brent Eberhard, Brian Ahlers, Paul Shively and Ben Rafferty.

The trip was co-led by Hoffman Institute staff member Benjamin Miller, a Missouri native who has worked extensively in the Ozarks in cave and karst research projects, including hydrology and cave survey, among other geological endeavors.

The purpose of the trip was to engage students in fieldwork related to fluvial, glacial, climatic and karst geomorphological processes and landforms, along with weathering and tectonic processes. The trip provided them with hands-on experience in studying and understanding these complex landscapes in a region that provides a natural classroom with diverse examples of geomorphology from 1.4 billion years of Earth’s history.

Nine undergraduate students participated in the course — Brian Ahlers of Louisville, Adam Aldridge of Bowling Green, Dane Black of Bowling Green, Brystal Dennis of Bowling Green, Brent Eberhard of Brentwood, Tenn., Michelle Foley of Salvisa, Ben Rafferty of Greensburg, Paul Shively of Owensboro and Brandon Thomas of Bowling Green.

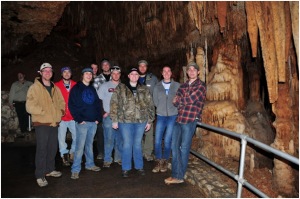

The group also visited Blanchard Springs Caverns in Arkansas. Front row (from left): Ben Miller, Dane Black, Ben Rafferty, Brystal Dennis, Michelle Foley and Brent Eberhard; back row (from left): Paul Shively, Brian Ahlers, Brandon Thomas and Adam Aldridge.

The group visited several distinct regions to gain a comparative understanding of various geomorphological processes and landforms. One major theme was visiting the karst region of the Salem Plateau, which formed in sedimentary rocks, to examine fluvial (river) and karst processes. The stops included Missouri’s largest spring and several smaller springs, the large losing stream of Logan Creek, and a visit to Onondaga Cave State Park to tour the spectacular evolution of an iconic Missouri cave system. Another stop for a different type of geomorphology included a long hike through the Pickle Springs Natural Area to see arches and canyons that formed in sedimentary sandstone bedrock.

The group’s other theme included the igneous geomorphology caused by volcanic and tectonic activity, which included several “shut-ins,” or constricted areas, that occur in streams when the harder igneous rock erodes away more slowly than surrounding rocks. The students also visited Taum Sauk Mountain, the highest point in Missouri, to learn about igneous glades and observe lichens, frost wedging and other erosive processes. A favorite stop was Elephant Rocks State Park to observe a large granitic exfoliation dome where elephant-size rocks remain after millions of years of erosion and weathering has rounded them out as they erode along weaknesses in the rock caused by “unloading” when pressure is released through tectonic uplift.

“It is sometimes hard to grasp concepts when you can’t physically observe those features,” said undergraduate geology student Michelle Foley of Salvisa, “but this trip allowed for the use of concepts taught in the classroom.”

Brystal Dennis, an anthropology major from Bowling Green, noted: “The trip to the Ozarks gave me a real-world view of dozens of geomorphologic features and the processes that cause them.”

WKU students at the bottom of Grand Gulf, a large collapsed cave system in Missouri. From left: Michelle Foley, Ben Miller, Brent Eberhard, Adam Aldridge, Paul Shively; back: Brandon Thomas.

Part of the course emphasis is to understand the linkages between the cause and effect relationships that occur in the landscape, such as feedback systems. Undergraduate Paul Shively of Owensboro said: “We paid close attention to the rates and processes, driving and resisting forces, and the resulting landforms,” which are all integral parts of understanding landscape evolution through the study of geomorphology.

“The students were engaged during the entire trip, as the Ozarks offers a rich and diverse natural classroom to teach about a variety of geology, hydrology, and environmental components that are fundamental to geomorphology and exciting to experience in the field,” said Dr. Polk.

“For a subject like geomorphology, getting out of the classroom and into the field is necessary truly to appreciate and understand the concepts. At each stop, we also discussed the human aspects of geomorphology in shaping our environment, which produces critical thinking about applied geomorphology in

Some of the links on this page may require additional software to view.