Gender & Women's Studies 20 Year Anniversary Awards Celebration

Happy 20th Anniversary Gender & Women's Studies Program!

Women’s Studies held a 20 year celebration on November 15, 2010 at 6:00 pm in the DUC cupola room. We celebrated the 20 year anniversary of the Women’s Studies minor.

Student comments from Kat Michael, Skylar Jordan, and Megan Green

Mary Ellen Miller's Commemorative Poem

Molly Kerby's Commemorative Song

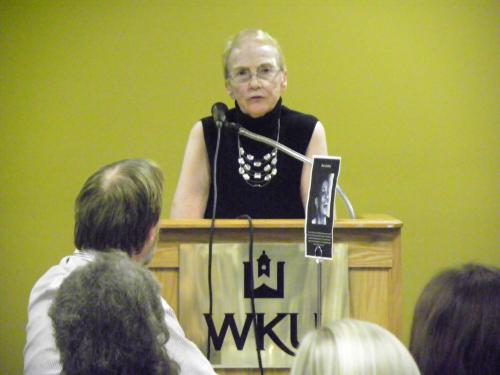

Jane Olmsted’s opening remarks:

The Birth and Promise of Women’s Studies, according to me.

Chapter 1

The confusion appears to have originated in the garden. Was she made from someone else’s rib and therefore subservient to him? Or, were these two human beings created simultaneously? Whichever way it happened she was the one who bit the apple. Across the vast oceans and in other lands, the accounts make no mention of the apple, and still somehow she bit it.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Chapter 2 “The First Feminist”

Chapter 2 “The First Feminist”

Once upon a time, a little girl named Mary was born into the world of 1797, and for 10 days she gazed at her mother, until her mother, also named Mary, died in a pool of blood from childbed fever.

Little Mary idolized her father but did not like her step-mother. Born into a world of famous writers, she had what many other girls did not: a literary role model. Even though her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was not there physically, she had shown her daughter how to resist the script culture had written for her. Sometimes called the “first feminist,” Wollstonecraft had published A Vindication of the Rights of Women, 5 years before Mary was born. In the Vindication Wollstonecraft responded with intelligence and no small amount of outrage to such notions as Rousseau’s “Little girls always dislike learning to read and write, but they are always ready to learn to sew.”

Mary Shelley

And oh how the critics latched onto her mother! One person, a Reverend no less!,

wrote that her beloved mother had “died a death that strongly marked the distinction

of the sexes, by pointing out the destiny of women, and the diseases to which they

are liable.”

And oh how the critics latched onto her mother! One person, a Reverend no less!,

wrote that her beloved mother had “died a death that strongly marked the distinction

of the sexes, by pointing out the destiny of women, and the diseases to which they

are liable.”

As it turns out the only sewing that Mary liked was in her imagination, and when the stitching was of body parts, the handiwork of her famous Dr. Frankenstein, who pushes the boundaries of science and the laws of humanity by creating his own human being, someone no one liked and everyone persecuted.

Chapter 3

One day our little girl looked down at her skin and noticed that it was much darker than the last time she’d looked—but still not as dark as the other slaves who lived in her town. The year is around 1830, and her mother, who was named Linda, had disappeared. The little girl sometimes sensed that her mother watched over her—which indeed she did.

Harriet Jacobs

Linda was hiding in a tiny attic where she crouched for 7 years, watching her children grow up in the yard below. Her narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, would be published after she and her children escaped, and become one of the first exposes of sexual harassment, something that all slaves, but especially women and girls, knew all too well. Like other slave narratives, Incidents required an introduction by a white person to confirm its authenticity, and became an indispensable tool in the effort to persuade white northerners to rise up against slavery. Publishing under the name Harriet Jacobs, Linda wrote, “I would ten thousand times rather that my children should be the half-starved paupers of Ireland than to be the most pampered among the slaves of America” (p.162).

While many slave narratives were by men and examined the emasculating effects of slavery, Jacobs’ narrative was for the women. She said: “Reader, it is not to awaken sympathy for myself that I am telling you truthfully what I suffered in slavery. I do it to kindle a flame of compassion in your hearts for my sisters who are still in bondage, suffering as I once suffered.”

Chapter 4

The next day, the little girl woke up (found her skin white again and her accent English). Her aunt, the beautiful and brilliant writer Virginia Woolf, had just published A Room of One’s Own. She’d already written other books and was a well-known defender of the rights of women. The little girl, though she did not yet have a room of her own, knew that someday she would. The year is 1929.

Virginia Woolf

Little Ginger liked to stand at Aunt Virginia’s side when she wrote, and sometimes

asked, “What are you saying now?” She loved the way the ink flowed from the pen and

hoped that one day she, too, would write stories. “What are you saying now?” I’m saying

that “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic

and delicious power of reflecting the figure of a man at twice its natural size.”

Little Ginger liked to stand at Aunt Virginia’s side when she wrote, and sometimes

asked, “What are you saying now?” She loved the way the ink flowed from the pen and

hoped that one day she, too, would write stories. “What are you saying now?” I’m saying

that “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic

and delicious power of reflecting the figure of a man at twice its natural size.”

“Oh, I like that one,” and Ginger turned the magnifying glass upside down so that her Cyclops eye filled her face. “What are you writing now?” she asked, when she tired of holding the glass up to her famous grandfather, who was writing an encyclopedia in the other corner.

I’m quoting a famous historian who tells us that in 1470, in upper-class families, “‘the daughter who refused to marry the gentleman of her parents’ choice was liable to be locked up, beaten and flung about the room, without any shock being inflicted on public opinion.’”

“I don’t like that one,” said Ginger, “please write something better.”

Aunt V. smiled. “If I keep reading to you I’ll never get this finished, so one more: ‘I told you in the course of this paper that Shakespeare had a sister; but do not look for her in Sir Sidney Lee’s life of the poet. She died young–alas, she never wrote a word. . . . Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word . . . still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed.

But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh.”

Chapter 5

The next day when she woke up, the little girl was back in the United States. Her two mothers were sitting together on the sofa. Her step-mother was holding her mom Audre close, though she had to be gentle because Audre had grown so frail. Beth watched them for awhile thinking about her famous mother’s work, and what she would do without her—since she knew her mother was dying.

She thought about how her mother had changed the world for black women and the women’s movement itself.

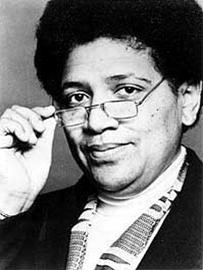

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde used to identify herself, saying “I am,” always reminding people, making

visible the parts of herself that would otherwise be erased—lesbian, mother, member

of the one-breasted clan of women warriors—A teacher! She taught hurt people to love

themselves. She taught:

Audre Lorde used to identify herself, saying “I am,” always reminding people, making

visible the parts of herself that would otherwise be erased—lesbian, mother, member

of the one-breasted clan of women warriors—A teacher! She taught hurt people to love

themselves. She taught:

About difference:

“It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.”

About change:

“Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women . . . know that survival is not an academic skill…For the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house.”

About silence and fear:

“I was going to die, if not sooner then later, whether or not I had ever spoken myself. My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you…Because the machine will try to grind you into dust anyway, whether or not we speak. We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and our selves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid.”

Chapter 6

She yawned. She stretched. She slipped her legs from beneath the covers and slid her feet into her Dora slippers. She called for her father, but he did not answer. She called again. A sliver of fear entered her heart. Then he answered. “You awake? I was out in the garage.” Dora ran to him. “When will I go to Mom’s house?”

Dr. Jane Olmsted

“Let’s have breakfast first and clean up and then I’ll take you there.”

Dora has already become accustomed to her new life in 2010. She assumes that her parents will care for her, that even though they live apart now, they will not desert her. Still she has dreams that wake her in the night, her arms clutching her pillow.

She does not know what others have been through, or what their cries in the night have led them to do. She doesn’t know yet about slogans like “Failure is impossible.” She will go to her Montessori school assuming that everyone else goes to a school just like hers. Her awareness will grow in different ways: in harsh, jangling sounds, in sad, tearful looks, and in burning pangs and full-body chills.

Dora will enter a high school that graduates the top students in the state. She will get a scholarship and graduate summa cum laude, and become an attorney, or a doctor, or a professor. She will run for office.

And lose. She will go on the speaking circuit.

Although they have not met, Dora has a cousin, named Nora, and she charts a different course. The nightly assaults cast a pall over her face, and by 15 she has left home, dropped out of school, and sleeps in her car or at a friend’s house. Her mother has another new boyfriend, and her father, who died in the Iraq War, has been gone for three years. She regrets that she has failed him and carries his picture in her wallet, kissing it when no one’s looking.

Will Nora be saved? Will she save herself? Perhaps she will run into one of her teachers, who will take her out for coffee and remind her that she has a wonderful mind. Or her father will come to her in a dream and tell her she is still precious to him. Perhaps she will slip into a reading at the local university, if only to escape the chill of night, and she will hear someone speak. The lectern is far away, but the words seem to be for her alone. In fact, the speaker looks directly at her, or so it seems. She says:

“Any woman who chooses to behave like a full human being should be warned that the armies of the status quo will treat her as something of a dirty joke. That’s their natural and first weapon. She will need her sisterhood.”

Sisterhood? Full human being?

Nora lowers herself into a seat in the back row.

“If the shoe doesn’t fit, must we change the foot?” Nora looks at her own feet, thinks how they have carried her here, though the shoes—well, she wouldn’t mind exchanging those. She feels an inside smile beginning to emerge and looks back at the speaker, who is saying,

“The first problem for all of us, men and women, is not to learn, but to unlearn.” Is that even a word? Nora wonders.

She reaches into the large pocket of the army jacket she’s wearing and discovers an apple that she’d forgotten was there. She lifts it to her lips and takes a bite. In the very moment when the speaker stops to take a breath, a crunching noise fills the auditorium. She looks at Nora. The whole audience turns to stare.

Nora swallows. “What?” she says, “I’m just unlearning this apple.” Somehow her words, which she intends only for those nearest her, reach all the way to the podium, in fact, are heard throughout the auditorium. The speaker shoots her fist into the air. 400 audience members raise their fists as well. Nora steps into the aisle and raises her apple, then bows low, curtsying so that her army jackets whirls around her like a gown. The applause is thunderous.

The End

There were founder comments from Carol Crowe-Carraco, Retta Poe, and Katie Ward.

Retta Poe

Remarks from Retta Poe: Women’s Studies Program 20th Anniversary

Most of us recognize that WKU’s physical environment – that is, the campus – has changed dramatically over the past 20 years. What many of you may not know is how much the cultural environment, especially for women students, faculty, and staff, has changed. Having joined the WKU family in 1974, I am in a position to remember how very different the local world was for women before Women’s Studies came along. To illustrate a few of those changes, I’d like to do a sort of George Bailey-“It’s a Wonderful Life” review of how our local scene used to be and how it might still be if not for Women’s Studies – and I’m counting all of the Women’s Studies programming, not just the undergraduate minor whose birthday we are celebrating tonight.

- First, within the larger community – that is, Bowling Green and Warren County: as of 1974 there had never been a woman as mayor of Bowling Green, nor had women been elected or appointed to governing bodies such as the Fiscal Court or City Commission. At the state level, there hadn’t been a woman as governor; I believe that Martha Layne Collins, who was governor from 1983 to 1987, was Kentucky’s first and only female governor.

- On campus, as of 1974 no woman had ever served as student body (SGA) president or as Student Regent.

- No woman had ever been the Faculty Regent.

- No woman had ever chaired what was then the top faculty governance body, the Academic Council.

- No woman had ever chaired the Board of Regents – and few women had even served on the Board of Regents.

- There were no support organizations for non-traditional women students, because Women In Transition had not been developed, nor was there anything like the Women and Kids Learning Together Summer Camp or any of the other formal and informal initiatives to support women students and prospective students.

- There was no scholarship program specifically for women students, such as Women’s Studies now offers.

- There were no programs to encourage girls to consider careers in fields such as mathematics, the sciences, and engineering, or even just to aim for high academic achievement.

- There was no support organization for women faculty and staff. I should add, though, that in 1974 there was a Faculty Wives Club.

- In 1974 women faculty members were clearly in the minority in nearly all departments. For example, fewer than one-third of the faculty in Psychology were women, whereas now the majority of the faculty in Psychology are women.

- Within Academic Affairs there hadn’t been any women deans or women in other administrative posts higher than department heads. Even among department heads there were very few women, mostly those found in what were considered the more traditionally “feminine” disciplines such as nursing. Even the heads of all of the departments in education – Elementary Education, Reading and Special Education, Secondary Education, etc. – were men, and the head of what was then called the Dept. of Home Economics and Family Living (now Consumer and Family Sciences) was a man. Since 1974, of course, there have been many women in top administrative posts at WKU, including provost, other vice presidents, deans, etc., and women have even headed up academic departments that have been traditionally considered men’s fields, such as engineering, chemistry, and business.

- Before 1978 no faculty member had ever received a paid maternity leave. I know this for a fact because I was told that mine was the first.

- There was no protection or redress for women students, faculty, and staff facing gender discrimination or sexual harassment, nor were there resources to provide assistance to victims of sexual assault.

- There were no permanent, established courses on women and gender. The first ones were established in the late 1970s: Women’s Literature, Women in History, Women’s Folk Life, and Psychology of Women.

- Finally, there was little or no recognition on campus of the value of scholarship on women and so-called women’s issues. There’s plenty of room for improvement even now, but it’s clearly better than it was, and I think that the advent of the Women’s Studies program and the success of the Women’s Studies conferences are largely responsible.

These are just a few examples, but they serve to make the point that a few determined people – in this case, mostly women, with support from a few enlightened men! – can have an impact to make the world a better place for those who come after. While some of the changes I have noted are a reflection of changes in the larger society, others are clearly due to the determined efforts of WKU women and men working in and for the Women’s Studies program.

Margaret Mead said it best: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.”

I know you join me in being thankful for the thoughtful, committed citizens of WKU who seek to change our world, and for the positive impact Women’s Studies has had on our campus and in our lives. ~

Katie Ward

SOME THOUGHTS ON THE WOMEN’S STUDIES PROGRAM:

by Katie Ward

Carol and Retta have given you a good outline of the history of women’s studies at WKU and of the many ways that the culture of the University has changed over the past twenty plus years. I have chosen a different topic: the key transformational moments for me when I was trying to get the Program established.

The first and most significant of those moments came a few days after the close of the first Women’s Studies Conference that I chaired, before we submitted a proposal to the Academic Council for a formal program. The conference had been grueling and exciting at the same time. Speakers had come from throughout the United States and from South Africa, Italy, and Belgium as well. I had been receiving calls at home at odd hours from various time zones to answer questions from these far-flung applicants.

But now I was finished. The checks had been deposited and the bills paid. With a sense of relief I stopped at my mailbox in the English office late one afternoon, ready to call it a day. There was an envelope with a personal check, signed with a name I did not recognize, a Val Scott from San Francisco, California. Here was a check for what seemed to be $10.00, which I presumed was a late payment for a luncheon. I tossed it into my book bag somewhat annoyed that I still had some follow up bookkeeping to do. Later that night I looked at the check again, and it was not for $10.00, but for $10,000, not from a conference participant but from a woman I did not know whose only request was that we not disclose her name. (She later gave us permission to identify her.) Then I remembered that Cam Collins had told me about someone who might be interested in making a contribution and that I had sent her a very brief award application for support. It turned out that Val was a single mother of two sons, who had inherited money from her family’s mining interests in Kentucky. Val had hired a journalist and a lawyer to investigate programs that were improving the lives of Kentucky women. Based on what she heard about us, she had selected to fund our group among a few others. Later on we were the only group that Val continued to fund.

I was dumbfounded by this support that seemed to come out of the blue. Someone believed in us!!! As Val continued to support us over the years, doubling her annual donations, she gave me the courage to go on in spite of widespread opposition, especially among mostly male administrators who thought that Women’s Studies had no place in a college curriculum and who feared that enrollment would go down in classes in their departments if students signed up for Women’s Studies classes.

When I got over the shock of Val’s contribution, I wrote her a letter expressing my deep appreciation and telling her what her belief in us meant to me personally. From then on from time to time, I wrote to Val to update her about what we were doing, and I would include copies of my students’ work in Women’s Studies classes. I was thrilled with their progress. I could see them gradually developing intellectually and growing in their awareness of themselves and their potential. They were finding their power and their voices. The world was opening up for them. Val must have shared my enthusiasm for the way that Women’s Studies was changing the lives of these young women because she continued to fund the program even after I had stepped down as Director.

In short, the second thing that encouraged me to continue to go on in spite of any indifference and opposition I faced was and simply still is, you, the students. You are what Women’s Studies is all about. You are the future, and you continue to inspire me.

I have always had a strong belief that Women’s Studies should be much more than an academic discipline, that the life of the mind and the transformation of the person should result in efforts to transform the world of the individual. And you are doing that. You are powerful agents of change. I am both proud and inspired by your leadership:

your women’s reading group at the Warren County Jail, your fundraising and mentorship in the Kids and Mothers Summer Camp, your lobbying for the benefits for domestic partners of University employees, and many more both personal and group initiatives.

We have so much to celebrate tonight, but our main celebration should be the products of the Women’s Studies Program–each of you. ~

Student comments from Kat Michael, Skylar Jordan, and Megan Green

Imagine a world where sexism on campus and in the community goes unaddressed. A world where women’s perspectives are lost, and patriarchy is not even included in the academic lexicon. Without Women’s Studies, our community would be much less enlightened.

Women’s Studies has allowed students to hear some of the greatest feminist minds from around the country. People like Gloria Steinem, bell hooks, Jean Kilborne, Allan Johnson, and Jackson Katz have all been brought to WKU thanks wholly or in part to Women’s Studies. Students also may not have been exposed to other great feminist scholars like Butler, Dworking, Daly, and Wollstonecraft.

But since knowing is only half the battle, one of the great things about Women’s Studies is that it gives students a chance to learn both inside and outside the classroom. It provides ample opportunity to apply theory to praxis, teaching students how to effect positive change in the world around them. Events such as the Women and Kids Learning Together Summer Camp, Take Back the Night, Eco-Feminism Day and Vagina Monologues not only provide much needed outreach but allow students a chance to learn through service.

Women’s Studies is a special place on campus. It is a place where students can share their experiences and learn about the societal forces at work in our world, addressing them in a way no other field does. It is a place where we examine ourselves and those around us, a place where we learn to make connections and grow as scholars, activists and feminists.

It is also a place where we have made great friends and been encouraged by wonderful mentors. Fostering a group of dedicated, progressive feminists is one of the most important aspects of the Women’s Studies program and is one of its most enduring legacies. Women’s Studies has opened many eyes and many minds, and has helped make WKU a more enlightened campus. The contributions of the faculty, staff, and students to the campus and Bowling Green community are invaluable.

So to all of our founding mothers, our professors, and all of the community members, minors, and graduate students past and present that have made this such a great program: thank you! ~

WS recognizes all our founders, donors, faculty, and most of all students for making this all possible!

Thanks to Mary Ellen Miller for the thoughtful commemorative poem.

Mary Ellen Miller

Women’s Studies at WKU: We Came to Stay

Written by Mary Ellen Miller, for the 20-year anniversary

Our flag is any color except white.

Our canon has one middle N.

We burned no cross on lawns

In dark of night for those who didn’t want us in.

For twenty years we’ve fought a bloodless fight,

A fight against the sneers and jeers.

There was no program here: no course, no class.

Our pioneers, many of them here tonight,

Survived the taunts to fire our shot heard

Round the world; to shine our light

Against the darkness of the night.

The dark of ignorance.

My great grandmother rode l5 miles on horseback

Through the dark and cold in l920—

So I’m told—to be the first to stand in line to vote.

I wonder: did she sing?

Did she fling her arm upward to salute that day?

Ninety years ago this year.

I like to think she did.

Where are we now at WKU?

Here and elsewhere we can vote.

We have a program where there was none.

Our Katie led the charge and then

There was Jimmie; and then Jane

And far too many more to name.

Who fought the Academic Council and the jeers:

“When we gonna get a Men’s Program?”

In l990? Surely not.

Tell them Katie, Carol, Retta, Judy, Jane,

And far too many more to name.

So here we stand.

We are here; we’re queer.

And we’re not.

We are here; we’re white.

And we’re not.

We are here; we’re women.

And we’re not.

Those brave, good men

Who helped us lead the fight—

Some of them are here tonight.

Salute!

We salute you now and all who fought

To make a dent in the bent, male-centered world.

We’ve never wanted more

Than what men have.

We’ll keep on coming

Wave after wave

Our daughters, nieces, and our friends.

Don’t lock the doors:

We’re coming in.

We’ll beat them down with fists

As raw as bloody meat,

With poetry, prose, and argument.

Every candle large or not

Is one that blazes toward the stars.

Every film, every talk, every class

Helps lead the way for those who cannot

See or say.

Our name is EVERY LITTLE GIRL

Who goes to bed in fear.

We are her name.

Let us in fairness be all one.

Let us adopt the name

WE-ALL-ARE-EVERYONE.

Let this be our motto:

We are here; we came to play.

We are here; by now you know

WE CAME TO STAY. ~

Thanks to Molly Kerby and Susan Morris for the wonderful commemorative song.

Susan Morris and Molly Kerby

The History of Us

Written by Molly Kerby (2010) for the 20th Anniversary of the WKU Women’s Studies Program

The recording of history is just recording the past,

but you know our history is much more than that.

It’s formed our agendas and our freedoms at last.

Separate from emotions our motives and acts.

Through the prism of oppression we all see the light.

Yet we carry our stories through unchartered flight

Beaten and defeated yet pride cannot budge,

the dead weight of hatred and offensive grudge.

Our history is then, Our history is now

A strange contradiction that makes sense somehow.

It’s the story of you, it’s the story of me.

The past and the future are all we can see.

It’s the story of us, the history of us.

We fight our good fights with our hearts in our hands

As we work for equity across the land.

We are more than scholars, we are fighters for peace

We look to the future for meeting these needs.

Events of our past roll through the tides of time

As we pass through them day and night.

Our heroes come and then they go

But each victory changes the hands they show.

We’ve survived misunderstandings

As we’ve aspired to gain our rights.

Time creates our history, this story of us

But it teaches us who we are and who we will become.

~

Some of the links on this page may require additional software to view.