Alumni Spotlight Archive

Spring 2021

Spotlight on: Gavi Begtrup

by Erika Solberg

Gavi Begtrup (VAMPY 1996-97; Travel to Paris 1997; Travel to London 1997; TA 1999) grew up in Nashville, TN, and earned a BS in physics, math, and computer science from WKU in 2002 and a PhD in physics from the University of California at Berkeley in 2008. He served as a staff member to United States Representative Gabby Giffords of Arizona from 2009-12. He co-founded his first start-up, WaveTech, in 2013 and led his second, Eccrine Systems, in 2014. He is currently running for mayor of Cincinnati, OH, where he lives with his wife, Dr. Amber Begtrup, a clinical molecular geneticist at GeneDx, and their three children, who are 11, eight, and four. He spoke with us during the week of winter storms this February.

Let’s start with the present. Why are you running for mayor?

Running for office has been in the back of my mind for the last decade, ever since I worked in Congress. I spent three years as the policy advisor for Gabby Giffords. That time was both awesome and terrible: I saw the wonders of what Congress can do for our country — we passed the Affordable Care Act, we worked on climate change, and I wrote legislation that changed the future of human space flight and changed the military’s consumption of energy. I also saw the worst of American politics and political violence when my boss and mentor was shot, and my friend and coworker was killed [Note: Giffords and 19 others were shot during an assassination attempt in Arizona on January 8, 2011. Six people died, including Gavi’s friend and coworker Gabe Zimmerman. Gavi was not present.]

When Gabby retired, I left politics. I moved to Cincinnati and became involved in entrepreneurship. Running for office wasn’t on my radar. Then, a few months ago, a member of the Cincinnati city council and the frontrunner in the mayor's race became the third member of the council indicted by the FBI for accepting bribes. It became clear that we have a culture of corruption — we have a city government whose members are more interested in lining their pockets than in growing the city. Meanwhile, we have a city that's been stagnant for a long time — we have the same size population we had a hundred years ago. Cincinnati is an awesome place to live, yet we're not growing. We also have tremendous inequality: we have two of the greatest companies in the world, Procter & Gamble and Kroger, yet we also have food deserts and 45% child poverty.

No one running for mayor was talking about the future of the city, about how we're going to address this trend in inequality, about how we're going to correct 50 years of racist policies that have created neighborhoods that are still redlined and still cut off from opportunity. No one who was running had executive leadership experience, and none of them had kids in the public schools. I decided it was time for something different. It's been a weird path from physicist to policy advisor to entrepreneur to political candidate and, hopefully, mayor.

If you become mayor, how would you fix the system of corruption?

The fortunate thing for our city is that we have an opportunity to change because our mayor's race is open — our current mayor is term-limited — and there's only one incumbent on city council who is still eligible for reelection because everybody else is term-limited. But these things don't change overnight. When I worked for Gabby, she had one vote out of 435 in the House. Her vote was only so powerful. Her bigger power was the ability to convene people and to lead on issues, and that's really the power of a mayor in a city like Cincinnati, where the position isn’t that of a chief executive who runs everything. The power is to set a vision for people to get behind and then hire the city manager and set a culture for city hall.

The biggest things I learned building companies from the ground up as a CEO are that culture is critical, and culture is set at the top. Cincinnati needs a leader who says, “We're going to change the way these things work.” Policy plays a role, too, but the current corruption is a symptom of a government that's not functioning correctly. I've run organizations where there has been leadership and ownership at every level. You empower your people, you organize them around a vision and cultural values, and then you empower them to go make decisions. You get so much more out of people when they are empowered to drive things.

So, for example, with the city council, what we want is to get everybody subscribed to the vision of Cincinnati becoming the capital of the modern Midwest — becoming the Queen City again, a jewel of the region. That vision means we need to be growing, and we need to be growing inclusively so that every neighborhood is included — so wages go up and opportunity goes up. If you get everyone to say Cincinnati could be bigger and better over the next ten years, then you have your destination. And then you're just figuring out the route to take. We can disagree on policies along the way, but I want everybody on the council, whatever party they belong to, I want them all subscribed to that vision. And that strategy requires leadership, which is only learned only through experience, which has been sorely lacking in Cincinnati government.

As mayor, how would you improve the schools?

I would be the first directly elected mayor in Cincinnati history who has kids in public schools. As someone who is a product of public schools, who went to Western Kentucky University and the University of California, Berkeley, both public universities, I think that’s ridiculous. Whether you send your kids to public schools or not, whether you even have kids, public schools are critical to our economy, and they're critical to our neighborhoods. People move out of cities that don't have good schools, and that means the tax base is lowered and the schools are hurt more. If you want equitable development, schools are the avenues.

In Cincinnati, the mayor does not run the schools — there's a separate school board and superintendent. But what we've learned in this pandemic is that school doesn't end with the last bell. We need support structures for families, and the city runs those. The city runs the rec center, before and after school care, and all these other things that make it possible for a kid to grow up and have opportunity. I believe that the mayor's job first and foremost is to say schools matter, so how can we support them? How can we build collaboration between the city and the schools?

What experience do you have in working with schools?

I helped build a school here in Cincinnati called the Donald and Marian Spencer Center for Gifted and Exceptional Students. It’s a public magnet school for gifted kids named after Donald and Marian Spencer, who were civil rights icons in Cincinnati. Gifted education is a predominantly affluent white thing that exists in wealthier schools, so the school district placed this new school in the middle of the city, in Walnut Hills. It hired a principal, and I reached out to her andsaid, “Gifted education is something I'm passionate about,” and I got involved. I talked about it a lot with Dr. Roberts. I became the board chair of the school for the first three years of its existence. We grew from zero to 350 students, serving kids all over the district. It’s an integrated school that looks a lot more like Cincinnati than most schools. It's majority minority. It's one of the greatest things that I've been able to be a part of.

Your education was non-traditional. What was school like for you?

I never fit well in school. Schools are built around the middle, but I was way on one side of the curve, and I just didn't fit. I loved learning, but I hated listening to people tell me something I already knew and then tell it to me again, and again. I would butt heads with teachers. Every once in a while I had a teacher who was truly wonderful and got me, but the structure of traditional school didn't work for me. The schools tried — when I was in elementary school, I was put in the gifted program, and I skipped fifth grade. I went to seventh grade at a magnet school for math and science, and I was involved in things — I ran for student president. But school never gave me what I wanted. So, I dropped out in seventh grade and cobbled together a homeschooled existence. I started going to community college at age 11. There was a whole community of homeschoolers in Nashville, so I was in a school collective and finished everything for high school in the next two-and-a-half years. Then I went to Western at 14. I lived in Rodes Harlin Hall, which was the co-ed Honors dorm. And it was awesome.

What role did your family play in you being able to follow your own path?

The only reason it was possible was that my father, who was a psychiatrist, was forced to medically retire at an early age because he was no longer able to work. That put him in a position where he needed a good project — and I was a good project. He really drove my education. He's an autodidact who loves learning and loves knowledge and really shaped how I thought. It was great. I'm pretty self-driven, but he enabled all those things to happen. He's the one who found out about VAMPY and got me into that. I was also preceded by my siblings. My brother went to Simon's Rock College — now part of Bard College — which is an early-entrance school — at 15. My sister ended up graduating high school a year early. But this history wasn't on my mind at the time as a 14-year-old: I was just ready to leave home and go to college.

What stands out to you from your experiences with The Center?

All of it! My first year I took Math and did Algebra Two. I learned the entire curriculum in three weeks, which was awesome because I was being homeschooled, so that meant I got to move forward. The next year, I did Creative Writing. Bruce Kessler was my Math teacher at VAMPY, and then when I went to WKU, I was a double major in math and physics, and Bruce was then my professor. I spent a lot of time with him, and I've kept up with him over the years — I just talked to him a few weeks ago. VAMPY was twenty years ago, and I still keep up with people.

I also remember it being a lot of fun. Obviously there were the classes, but VAMPY is also where I discovered a love for Ultimate Frisbee and where I started playing card games. We would play Hearts and Spades and things like that. I had done traditional summer camps and enjoyed them, but at VAMPY, it was so fun to be surrounded by people who had something in common with me and were something like me. It was unusual for me. VAMPY is also the reason I went to WKU.

The other thing is the travel. I still have fond memories of both trips. My wife and I went to Paris and Bordeaux in 2016, and I recognized sites like Napoleon’s Tomb. It was amazing to be able to see the world and have that level of independence and high expectation for maturity. Everyone else had told kids like me that we were immature because we couldn’t pay attention in class or made inappropriate jokes or whatever, but then we had Dr. Roberts who said, “I believe you're mature enough to handle being in a hotel 10,000 miles from home and away from immediate adult supervision.” If you let people be responsible, and you set an expectation that you believe they can do this and you’re going to support them no matter how it turns out, you'll get great things out of them. And that goes for 14-year-old kids, too. At the time I just thought, “Oh, sweet. I'm in a hotel room. And they believe in me — they believe that I'm going to be good and that I'm mature.” And it worked.

How has the pandemic been with three young kids?

One reason why I make the point that I’m the only one in the mayor’s race who has kids in school is that the uncertainty during the pandemic has been really hard for young families. For example, my third grader’s school was remote at first, but then they went in two days a week, then it was remote again, then it was back to two days a week, and now it's snowing and so she can't go to school — but instead of having a snow day, her school is having a remote day,. That just doesn't work at all. I kept making the point to the school board that what families need is consistency. I said whatever you do, pick a system and stick with it, because changing is hard. If families figure out how to get work done and take care of their kids, and then you change it to some other system and they have to work out something new, and then three weeks later you can change it again, that's terrible.

I learned in Congress that what people hate more than a policy they disagree with is inconsistency in a policy. I made that point as a businessman too. Republican staff or friends would tell me that businesses hate regulation, but I said, “No, businesses don't mind regulation. They might not like a regulation, but what they really hate is uncertainty in regulation where everything changes every year or every three months.” It’s the same with families: we may not like being remote or being blended or whatever else, but stick with that system so that we know what to expect.

You tend to take on challenging projects that come with a lot of risk. How did you develop a mindset of being okay with aiming big, even if not everything works out the way you want it to?

I don't spend a lot of time thinking about failure because failure will take care of itself. In grad school, you fail constantly. When you're doing research, particularly in a science PhD program, most things will fail. Most experiments do not give you useful outcomes. And so I spent six years in grad school working a hundred hours a week doing research, and almost everything I did failed. You only get a PhD for discovering something that nobody in the world knows yet. When you're out on the edge, out in the wilderness exploring, you have to accept that you’re going to be poking around blind a lot, and you can call that failure, but what you're looking for is that one gem that will let you expand the realm of human knowledge. There is a moment in scientific discovery where you’ve figured out something and realize you are the one person in the world who understands it. And then you get to do something even cooler, which is to share it with the world. So I never thought in terms of success and failure; I just realized that you have to keep going until you find something that works.

In Congress, it was the same way. Thousands and thousands of pieces of legislation get introduced, and most of them have no chance of success. Things take forever — I mentioned the Affordable Care Act earlier: Representative John Dingell had been introducing a healthcare reform bill for 50 years before it happened. We tend to tell stories of successful people as if they did this successful thing, then they did another successful thing, and now they're billionaires. It's a lie — it's a disservice to society and to young people because that will not be their experience; they will fail over and over and over again, but if they give up, they'll never do anything great. If you don't keep pushing, you can't change the world.

I didn't have words for it when I was young, but I always saw a world that I thought could be better. I’d say, “Those traffic lights aren’t timed well.” I'd see lines at grocery store registers and say, “Why don't we have one line that feeds into all of them? I thought about efficiency and optimization a lot. My interest in research was to try to expand human knowledge. It's also why I went to Congress. I felt that doing research didn’t improve people's lives enough, so I did the exact opposite: I went from individual atoms to billion-dollar budgets. I had a tangible impact on policies that changed our country, even if my impact was a tiny little piece on a big policy.

When I started companies, I only wanted to work on things that could make a difference. My first company was an agricultural materials company, trying to improve greenhouses and cover crops because we continue — a hundred years after the green revolution — to have a challenge making sure that we have enough food and affordable food to feed people. My second company was a medical device company trying to improve diagnostics so that we could have better real-time health information without drawing blood. You can look at those companies and say, “Well, you failed; at the end of the day, your companies didn't succeed.” That’s true: we didn't have the financial outcome we wanted. With Eccrine Systems, the pandemic had a big impact — but we created a new field of medical diagnostics, had over 70 patents, and led the world in research and development. It is still my hope that in the future, somebody will make this concept profitable.

I'd rather try to do big things, fail 50 times, and then make a difference on the 51st than to never try to make a difference. People ask me why I'm running for mayor because I’m running against people with big names and the odds seem long. They ask, “Why do you want to go into politics? You don't get paid well. You get beat up by everybody. People will say terrible things about you that aren't true.” The answer is that I think I can make a difference.

Spring 2021

Spotlight on: Cat Gallagher

by Erika Solberg

Cat and king penguins at Volunteer Point.

Cat and king penguins at Volunteer Point.

Originally from Louisville, Cat Gallagher (SCATS 2007, Travel to Paris 2009, Travel to London 2010) earned a BA from Fordham University in 2017 with a major in computer science and minors in French and philosophy. In fall 2020, she moved to the Falkland Islands for six months to work for the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI), which conducts research in the natural and physical sciences in the South Atlantic from the tropics down to the ice in Antarctica.

Tell me about the work that you are currently doing.

My official job title is GIS officer — GIS stands for Geographic Information Systems. I provide mapping support for a lot of the different projects that are going on. I’m also the IMS-GIS (Information Management System and Geographic Information System) Data Centre manager: I manage the repository of all the data that's been collected during research in the Falklands.

Prior to 2013, researchers would come here, they would do research, and then they would depart without leaving a record of it. There was no chance for collaboration. Then the data center was formed to start keeping better records and keep track of the metadata, and that eventually evolved into the current data portal (dataportal.saeri.org). My job is to maintain it and to track down the people who did research in 2020 and upload their data, because there was nobody in my role for a year. I'm also building a data portal for St. Helena, which is another UK overseas territory in the South Atlantic.

I'm working on a ton of different projects right now. I am building a web GIS project for an ongoing project studying the wetlands in the Falklands. I'm updating another project mapping all the data for a marine management area — we have a lot of fisheries around the Falklands, so this project keeps track of the impact of fishing and other human activities on marine biodiversity. I'm also making maps for the Department of Agriculture because it’s trying to get farms certified to the Responsible Wool Standard, which will allow them to fetch a premium for the wool that they sell.

Why is the Falklands such a great place to do research?

It's unlike anywhere in the world. Researchers can have a base in Stanley, which is like living in a little village in the UK. But then you step right outside of the town, and there's untouched wilderness everywhere. If I drove 15 minutes from where I'm sitting now, I could get to four different penguin colonies. It's mind-blowing! I’ll go on a walk and see Commerson's dolphins playing around. The other day there was a sea lion hanging out.

There are a bunch of different islands, too. East Falkland and West Falkland are the two big ones, and there are also little ones that you can zip to on six-passenger planes. We have researchers who left today to do marine surveys on one of the little islands: they’re going to be scuba diving and surveying the seabed. It's such a rich area, and there's so much to study because it's a unique ecosystem. Once, I went out to see a king penguin colony that was on a working sheep farm, so there were penguins and sheep crossing paths.

What is a typical day like for you?

Most of my day is spent at the office working on different projects on my computer and going to meetings. One cool thing is that everybody goes home for lunch because we live two minutes away from work. And then after work, the main thing we do here is go for walks — they're not quite hikes, but they're more intense than a walk because you're usually trudging through tussock grass, which can be ten feet tall, and you’re not on a foot path — you might be following an off-roading track that a car has made. I go out to places like Surf Bay and Yorke Bay to see penguins and then come home and make dinner. Internet is limited, so we do a lot of downloading when we have free internet from midnight to 6:00 AM and then watch it later. The Falklands has been able to keep COVID under control, so on the weekends I can go out — I did pub trivia last night, and we won, which was awesome. I won ten pounds!

Tell me about your penguin encounters so far.

You can see the penguins everywhere. I’ll be walking along and one will end up in the path, and I’ll wait and be like, “After you,” and the penguin will look at me and be like, “After you,” and I’ll be like, “Well, one of us has to do something here!”

Also, the tourism industry relies on cruise ships, and during the pandemic there have been no cruise ships stopping here, so the government decided to give every person who's a resident — which includes me, even though I'm a contractor — 500 pounds to spend at tourism-related businesses. The most highly sought-after trip is to go to is Sea Lion Island, which is a remote island that’s only inhabited during the summer. The only thing on this island is the lodge. I went there in December using my TRIP (Tourism Recovery Incentive Programme) scheme money, and it was the coolest place I've ever been in my entire life.

I fell asleep to the sounds of penguins because there was a colony of gentry penguins outside the door of my hotel room. The noise they make is like a rubber chicken deflating, like a “Oooghh.” So imagine a thousand of those “oooghhs” — that's what I fell asleep too. Then I walked along the beach, and there were elephant seals everywhere. There was a colony of rockhopper penguins as well. On the way, looking down from a cliff, I could see sea lions. I had seen California sea lions in zoos, but those are so small compared to these! These sea lions were males, and they looked like lions and roared like lions.

Cat finds a juvenile elephant seal in tussock grass on Sea Lion Island.

Then I had my lunch next to the rockhopper colony. Penguins don't have land predators, so depending on the penguin, they're not super wary of people. They just ignore us. Some types are a little nervous, but the Rockhoppers just bopped along past me while I ate my sandwich.

The island has another bird called a striated caracara. They are giant birds of prey, and they are smart. As I was eating my sandwich, they were like, “She's going to drop something.” So they stood six feet away from me and waited, and when I dropped a piece of cheese by accident, one of them swooped in and grabbed it. And then this big, scary bird just looked at me. On my way back, I wandered too close to a caracara nest. I realized I had done something wrong because two of them ran down toward me — they didn't fly, which was also disconcerting. They stared at me. I didn't know what direction to move in because I didn’t know where the nest was, so I picked a direction and started walking. I picked wrong because the caracara divebombed me and kicked me in the head. Then I picked wrong again, so it divebombed my backpack. Eventually I was able to walk away, and they were like, “Yeah, that's right. Move on!”

What do you remember about your experiences at SCATS and travelling with The Center, and how have they influenced you?

SCATS was super fun. I had a great time and learned a lot, and it was nice to be around other people who wanted to spend their summers learning. I also really enjoyed the trips. Dr. Julia runs a tight ship — she had our schedule jampacked. We saw everything we could possibly see in those weeks. That's the kind of trip I love — “Since we flew all this way, let's see everything!”

In general, traveling with The Center made moving to the Falklands less scary. I probably wouldn't have come here it if I hadn't had the opportunity to travel before. I learned that new places are exciting, and it's cool to get to know people who are different from you. The trip to London has especially come in handy because I'm surrounded by people from the UK here.

How did you develop the skills and interests that led you to doing this work?

I majored in computer science at Fordham University, in the Bronx. What I like about computer science is problem-solving, but I realized in my senior year that the idea of following the usual trajectory of working at a tech company left me feeling empty. This happened in November of 2016, and the feeling coincided with a realization that climate change is not going to get fixed by itself — we have to do something. So I did some soul searching and thought, “What I would really love to do is work with animals and work on addressing climate change. How can I do that?” I spent a month Googling, looking up combinations like “computer science and animals” and “software engineering and wildlife.” Eventually I stumbled upon GIS. After I graduated, I took GIS classes and worked at Prospect Park Zoo for a year. It was so much fun — I did birthday parties, I handled chickens and lizards and snakes, and I showed animals to kids.

Then I realized I didn’t want to live in New York City anymore — it was too cold. It hit me that I could move to Austin: I had a friend getting her PhD in chemistry at University of Texas (UT), I had a degree in computer science so I could probably get a job, and I liked queso! I moved to Austin sight-unseen — I'd never been to Texas before I arrived there with my dog, Ally, and everything I owned. I got a job working at ForeFlight, which is an aviation app that pilots use in the cockpit. I worked with the maps, importing them from the FAA and processing them into a format the app could handle. It was great work, and I made good money, but I still felt empty. I still felt that pull to work with the environment.

So I was working from home, somewhat miserable, and then I got an email from a listserv from theSociety of Conservation GIS. I had always meant to unsubscribe because I never opened any of the emails, but I hadn’t. As fate would have it, that email was about the job with SAERI. My dad and I had gone on a cruise in 2016 and stopped at the Falkland Islands for a day, so when I saw the job listing, I thought, “I've been there. It was cool — we saw penguins.” I decided to apply, I got the job, and I arrived here in November. And as of yesterday, I am planning to start a master's in geography at UT in the fall.

What are you hoping to work on in graduate school?

I would love to work with endangered species and habitat mapping — biodiversity-type conservation work. I would love to be able to do some fieldwork where I get to work with animals. I am so jealous of my boss — he just got back from doing a seal census where he went to all the different islands and anesthetized seals so he could tag them and do a census. I was reading his research permit, and I thought, “Who gets to do that? That's so cool!”

You have taken some big leaps in your life, both in terms of moving around a lot and in your career decisions. What has helped you to be brave enough to make some of these big moves?

The reason I've been able to do all these jumps is that I had a support network. My dad's been so supportive. He’s from New Jersey, so when I moved to New York, I had family in New Jersey 45 minutes away. When I moved to Austin, I already had a friend there, and my sister came to help me move. And then moving here, I had already been here once, and I knew I was only coming for six months, and my friends’ parents were able to take my dog while I was gone. So yes, I was brave and all that, but it's because I have people to help me.

I think I also lucked into a good path with my career because what I'm finding is a lot of people in environmental science have their expertise in the physical sciences like biology or chemistry. Then they discover that it would be great to know how to code, so they have to pick up coding as they go along, whereas I'm going the opposite direction.

Often, young people feel they have to follow a single trajectory without realizing you can actually shake things up.

Exactly. I had always thought you have to go to college and major in something you’re good at. I was good at computer science, and I liked it. Then, when the end of college was looming, I realized, “There's no structure anymore. I can do whatever I want.” And it was terrifying. I’d never thought about what happens next, and then those doors opened up, and I thought, “Oh no, I have to figure something out.”

An interesting fact is that there are more women in every field STEM field now than they were in 1980 except for computer science. I didn’t love being the only woman in some classes — it was definitely harder. I had to seek out the other women or the guys who I became friends with. I think that that has played a role as well in why I've moved away from a pure tech career. At my job in Austin, when I got hired, I was the only woman, and by the time I left, there was one more. The job I have now has much more of a balance, and I like that better.

But I have always had a mix of interests. I have always liked the sciences, but in school I also did theater and speech and debate team. I've always wanted to do both. Geography and GIS are ways for me to use my coding skills to tell a story, which is something I really, really enjoy.

Is there anything else you're hoping to get to do during the time you have left in the Falklands?

I'd like to explore more of the islands. I haven't seen an albatross yet! I know that when I go back, things will not be back to normal from the pandemic, so I'm soaking up the experience of being able to just go over to a friend's house or go out to a bar or a movie theater. One of the first things I did here was go to the movie theater here and eat popcorn — I want to watch as many movies in the movie theater as I can while I'm here because I don't know when I will get to do that again when I get back to the U.S. And I want to just explore — there’s people who've lived here for 20 years who still haven't seen it all.

Cat with king penguins at Volunteer Point.

Cat with king penguins at Volunteer Point.

Late Fall/Early Winter 2020

Spotlight on: Khotso Libe (Super Saturdays 1999-2000, SCATS 2000-01, VAMPY 2003-04, Travel to London 2002, Travel to Paris 2003)

by Erika Solberg

Khotso Libe

Khotso Libe

Khotso Libe is a systems analyst in the Division of Strategic Enrollment Management and Student Success at the University of Louisville. He earned a BA from Louisville in 2010 with a double major in Pan-African studies and psychology, a Master of Education in college student personnel in 2013, and a MBA with a focus on data analytics in 2019. Prior to his current position, he was a senior academic counselor for the College of Arts and Sciences at Louisville.

We interviewed Khotso as part of our article “Closing the Excellence Gap: Friends of The Center Share Their Stories” in the Fall 2020 issue of The Challenge and wanted to share the full interview here.

Where did you grow up and go to school?

I grew up in Bowling Green. I went to Natcher Elementary and Drakes Creek Middle School and graduated from Greenwood High School.

Did the schools you went to have many other African American students, or were they vastly white?

Vastly white. Even now they don’t have that many students of color.

Did you have any Black teachers?

I had Mr. Stokes in elementary school — he was the PE teacher. At Drake's there was a Black man who was a guidance counselor and taught some classes. At Greenwood, I had two Black women, Ms. Townsend for freshman year English and Ms. Butz, who taught a keyboarding class. That was it. I can count them all.

Do you feel like at any point going through elementary, middle, or high school that you were underestimated?

Sometimes, yes. But being involved with The Center, starting in elementary school with Super Saturdays, gave me some internal “Oh, I can do this. I'm capable.”

One of the things that was upsetting for me was at Drakes Creek I was placed in Pre-algebra in eighth grade when I should have been in Algebra One. But then VAMPY gave me the opportunity to get my Algebra One credit: I took Math at VAMPY the summer before ninth grade, and it put me on a trajectory to complete AP calculus my junior year in high school. It meant a lot to me that I got to do that because math was my favorite subject throughout high school, and I started college as a math major.

What were your friendships like in school?

I was unique from my peers because I was living a couple of different lives, especially as a student of color at this predominantly white high school. There was a handful of Black males in my class, so I hung out with that group. I also hung out with the other Honors kids and had great friendships with them. I did track and field as well. I happen to be pretty friendly, so I had friends in a lot of the corners of the school — I was our student council president. My friend group was mostly from my school until about sophomore or junior year when I started branching out and had a good amount of friends at Bowling Green High — some folks of color, some not.

Did your family expect you to excel?

I was mainly raised by my mom, and she had high expectations for me. She gave me the opportunity to participate in The Center’s programs, which were things that I wanted to do as well. She expected me to have high grades: Cs weren't acceptable for her. I guess she saw something in me. It was huge to have my mom expect a lot and help me have opportunities, like to go abroad with The Center.

I started realizing that having my mom was a difference-maker in high school, especially when my pocket of black male friends didn't have parents who had those same levels of expectations, who didn’t take them on trips to go visit colleges and look up scholarships and things like that. I wasn't doing that stuff on my own: it was definitely my mom, exposing me to these programs, pushing me to do these programs, encouraging me, and giving me these opportunities to continue on with my education. Out of my black male friends whom I'm still friends with today, I was the only one who went off to college. I had unique opportunities, and I attribute all of that to the environment my mom put me in and how she helped me outside of school.

What was college like for you?

A lot of my cultural development journey happened at Louisville. For the first time, I was at school with a significant amount of Black folks with whom I could be entrenched in a community. I knew I wanted to at least minor in Pan African studies, after taking a class and being with Black teachers with an almost all-Black classroom — something that I'd never been exposed to before. We were studying some of the proudest moments of Black history and culture. Also, in freshman year I was involved in starting a group called the Student African American Brotherhood (SAAB). We promoted student success and the image of the Black man, combated negative stereotypes, and talked about what it means to be a Black man in society. We met every Wednesday dressed in professional business attire — shirt, tie, jacket — if you had to borrow something from another member, we made it happen. We were young Black men learning together how to be professionals.

I ended up double majoring in psychology and Pan African studies, and I was heavily involved in the Black community at Louisville. Not only did I end up being president of SAAB, but I was a peer mentor for Connect, a mentoring group where African American upperclassmen mentored first-year African American students. I was also involved with the Association of Black Students as vice president. Louisville created an environment where I could thrive and grow in a safe space with other students of color. Something that we talked in SAAB was being a leader not only in the Black community but on the whole campus, so I did some things with student council and student government as well.

Overall, I’d say college is where things really started to change for me. I grew a lot culturally. Even as I declared Pan African studies as a major, I was starting to grow locs — I just cut them last year, so I had them about ten years. I also was able to go to South Africa for the first time to see my family when I was in undergrad. I was culturally immersed, and that helped me to find who I am.

Did you feel pressure to succeed when you were in high school or in college?

Absolutely, especially in the AP classes where I was the only Black student — I felt like I had to represent the culture. If people were thinking about how Black kids did in that class, I was going to be the face that popped up. I didn’t have the language for the pressure I felt until later: stereotype threat. People did not always expect for me to do well. I felt it even when it was not real.

In college, we were presented with the numbers of how students of color were graduating at much smaller rates than white students, and the numbers for Black males were even lower. The six-year graduation rate was 35-40% university-wide, but for black males it was 10-12%. When we started SAAB, we knew it was not likely all of us were going to graduate together or graduate in six years. We used that knowledge to stick together, help each other out, have study sessions, and check on each other. And that was huge.

So I had a great support system in college, but the pressure to succeed was persistent. I saw students drop out every semester. I felt the constant pressure that “you're not done until you're done.” There’s a track reference I used: you have to run all the way through the finish line.

Given your own experiences, are there any things that you think that schools, from elementary all the way to college, could do better or differently to better support gifted African American students?

My teachers and classmates were all supportive, saying “You belong here.” When I didn't feel like I belonged there, it was imp to have those extra voices saying, “You don't see what I'm seeing here. You do have the potential.” Students of color can get imposter syndrome early, so being able to recognize it is helpful. It’s not unique to students of color, so that message could be for anyone in a high level classroom — that you are here for a reason — it can encourage students even when they may not have that pull in themselves.

Something that was surprising to me when I was mentoring first-year Black students was their reluctance to try the Honors program. Some of my mentees were great and had the GPA they needed for Honors, so I’d tell them they should apply, but they would say, “No, no. I'm not an Honors student. I don't belong there.” I’d say, “Yes, you do,” but there would be something in them where they'd already made up their minds that they weren’t. So it’s essential to have those messages echo throughout your schooling that acknowledge your strengths and say you can succeed.

Also, what made college different from elementary, middle school, and high school was that it had a critical mass, so we could pull Black students together. That's important — we see that with Black fraternities and sororities in higher ed — that's how they got started, and that's how they sustain themselves, getting a group of people together who share a mission that that mission should be succeeding. Some Black fraternities and sororities were formed at predominately white institutions, so it’s important to get those folks together to build that community so they can succeed together and support each other at the same endeavor. It would be great to have a critical mass of Black gifted students at elementary, middle, or high schools to support each other.

Anything else you want to say about The Center programs?

SCATS and VAMPY were memorable, life-changing experiences. It was a great community with engaging classes that kept you stimulated, and of course the fun activities like the dances and Capture the Flag. I got a college experience early. Also, the trips to England and France were my first opportunities traveling abroad and opened my eyes to things outside of America for the first time.

I'm thankful for the programs. I think about those experiences regularly, and about

some of those friends I made. My last year at VAMPY, there were four of us who were

Black males. We called each other One, Two, Three, and Four, referring to how many

Black men were there the year each of us came to camp for the first time. Fark Tari (VAMPY 2001-4, Counselor 2007) was One because he was the only Black male at one

point, I came in the next year so I was Two, Mzee Bw'Ogega (VAMPY 2003-04) was Three because he came the following year, and Dexter Heyman (SCATS 2003, VAMPY 2004) was Four the next year. Dexter’s year was the first time

that there were four of us, and that made it special. I have a picture of us where

we're holding up the numbers one, two, three, and four. Through that comradery, we

ended up being friends for years.

Fark Tari, Khotso Libe, Mzee Bw'Ogega, and Dexter Heyman at VAMPY in 2004.

Summer 2020

Spotlight on: Paul Hudson (SCATS 2010, VAMPY 2011-13, Gatton 2013-5, Counselor 2015)

by Erika Solberg

Leandra and Paul

Paul Hudson graduated from the University of Alabama-Huntsville in 2018 with a degree in electrical engineering, computer engineering, and optical engineering. He is a hardware/firmware engineer for Pulvinar Neuro in Durham, NC. He has joined the ranks of campers and counselors who met their spouses at VAMPY because he is engaged to fellow alum Leandra Caywood (VAMPY 2010-13), whom he met in his first year at camp. She is working on her Ph.D. in chemical engineering at North Carolina State University. He is on Facebook as Paul Hudson

Where have you been spending the pandemic?

I moved to Raleigh, North Carolina, at the beginning of February. My fiancé, Leandra Caywood (VAMPY 2010-13), had been living here in an apartment on a grad student salary, so I moved in, and we’ll upgrade in a couple more months. It was weird going from not seeing her regularly for eight months and then we're stuck in this apartment together!

Tell me about what school was like for you growing up and what regular school was like for you.

I grew up in a small town called Fairdealing. It’s east of Benton, in Marshall County. I went to the public schools — they were very flexible, so I was thankful for that. For a lot of my time there, I didn't have a good crowd that I was able to hang around with consistently, but as far as schooling went, from kindergarten on, they let me take advanced math classes, they let me take advanced reading classes — whatever I needed.

What was your first association with The Center for Gifted Studies?

My late grandmother, Kay Willis, was a teacher and was good friends with Dr. Roberts.

What do you remember about SCATS?

I was so happy to go to the camps every time I went. The first time, when I went to SCATS, I was surprised at how fun the classes were, because obviously you pitch this to a kid as, “You're going to a summer camp where you're going to be taking classes for two weeks.” One of the classes I took had a great title — it was Geology and the Movies. We discussed geological concepts and watched movies and tried to see how movies got it right or wrong. I also took a class on Pearl Harbor and a class on the Holocaust. They were all so interesting. I had never been in a situation where I’d been exposed to so much knowledge so quickly, and I really enjoyed it.

What about VAMPY?

VAMPY was even better than SCATS for me because at VAMPY I met some really good friends. I felt so at home. After the first year, I had to beg my parents to let me go back the next two years year because they wanted to be fair to my sister who only went one year — but then she said, “I don't care what he does.”

I had so much fun, and there were a lot of great people whom I met there whom I would have never met otherwise — and of course, my fiancé and I met there. Class time took up most of the day, but it didn't feel like class was what most of the VAMPY experience was. I got to learn and got a lot of good stuff out of those classes — after I took Math, my school district let me move on to calculus — but VAMPY also helped me grow as a person. Before I went to camp, my middle school teachers called me “squirrely.” I was the smart kid in class. I was kind of friends with a lot of people, but not good friends with many. It gave me a really good outlet.

What was it like being a counselor after you had been a camper?

I loved it. After being a camper for three years, I got a sense for how the camp is run, and everything that's going on and what the camp experience should feel like. I really enjoyed being able to give that experience to younger campers. I hope they enjoyed having me as a counselor. I still talk to two of my campers and play video games with them. One of them has graduated college and the other has almost graduated.

What started you in the direction of study you pursued and the career path you are on?

I was lucky enough while I was at Marshall County to take a pre-electrical engineering class. I thought it was neat. While I was at Gatton, I took electrical engineering classes, and it was those classes that really set me on this course because WKU was really good for beginning electrical engineering. They had a lot of hands-on lab experiences — I was able to completely design a circuit, from start to finish, and make it on a printed circuit board before I was even a college student. I also loved all the math and computer science classes I took at Gatton — the computer science classes were more eye-opening than almost anything else I took. Uta Ziegler, the computer science professor, drove home that computer science was basically a lot of logic puzzles, and programming languages are just syntax to solve those puzzles. I love that concept. It's helped shape my career and what I wanted to do — it’s what drove me into doing both electrical and computer engineering as an undergraduate.

And now you're working on some cutting edge biotechnology for Pulvinar Neuro in Durham, NC. Tell me about that.

Before I joined Pulvinar Neuro, I was working for a missile defense contractor in Huntsville, AL. I wanted to get out of the industry, and I also needed to move to Raleigh so I could live with my fiancé. I had always been interested in biotech and biomedical applications because that's where a lot of interesting work is done in my field. I happened across a startup company that was hiring in the Raleigh area and where I could do some hardware and some software and be able to freely design what they needed. I’m thankful that the work is so applicable and important.

When I started working for Pulvinar Neuro, it already had a rough, research version of its device that does two things, and— transcranial alternating current stimulation tACS and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Psychologists are researching to see if tACS can be used to treat different conditions in the brain like Parkinson's, depression, anxiety, and other illnesses. The thinking is that your brain has regular electric waves to make it work right, and certain people have deficiencies in some of these signals, based on chemical deficiencies in their brains. If we can pinpoint the signal deficiency in their brain, if we can read what's going on and then apply a current — a wave — to jumpstart that signal, we could use the device to treat those brain conditions.

A lot of people have tried to label transcranial stimulation as New Age shock therapy, but the device is at a very low current that is not noticeable to the patient. We have safeguards in place so that if the current ever became too intense, the device would stop. Right now, the device is made to do basic T-ACS and T-DCS in double-blind research studies. What I'm doing upgrading the software and hardware for the second version. We're working on getting it to read an EEG from the brain, so it can detect those signals and apply the stimulation that might be needed.

Is there anything else you want to share about your experiences at camp or your life?

I want to drive home that the connections I made at camp and at Gatton have lasted longer than others. There's still a group of people that I talk to from Gatton, and a lot of those people I knew from VAMPY beforehand. The programs opened up so many doors to me — I first learned about Gatton from SCATS, and when I was moving to Raleigh, I already had connections here with a former camp counselor and a fellow camper. The programs have been more instrumental than I could have ever imagined.

Winter 2020

Spotlight on: Erica Newland (SCATS 1998)

by Erika Solberg

Erica Newland (SCATS 1998) graduated from Yale University in 2008 with a BS in applied mathematics. She was a senior policy analyst at the Center for Democracy

& Technology for three years before attending Yale Law School, during which she worked

for the National Security Division at the Department for Justice and the Senate Judiciary

Committee. She received her J.D. in 2015 and went on to serve as a law clerk for the

Hon. Merrick Garland on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and as an

attorney-adviser at the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice. She

now works as counsel for Protect Democracy, a “nonpartisan, nonprofit organization

dedicated to fighting attacks, from at home and abroad, on our right to free, fair,

and fully informed self-government.”

Erica Newland (SCATS 1998) graduated from Yale University in 2008 with a BS in applied mathematics. She was a senior policy analyst at the Center for Democracy

& Technology for three years before attending Yale Law School, during which she worked

for the National Security Division at the Department for Justice and the Senate Judiciary

Committee. She received her J.D. in 2015 and went on to serve as a law clerk for the

Hon. Merrick Garland on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and as an

attorney-adviser at the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice. She

now works as counsel for Protect Democracy, a “nonpartisan, nonprofit organization

dedicated to fighting attacks, from at home and abroad, on our right to free, fair,

and fully informed self-government.”

What do you remember about SCATS?

It was the longest I'd been away from home, and I went with my very best friend, who ended up moving away the following summer, so it’s one of my last memories of us spending a lot of time together. It's very special to me for that reason, as well as others. I took a class in genetics which I remember the most clearly, and a class on acting with Julie Roberts. In all of my classes, it was wonderful to be with other kids my age who were also interested in spending time learning new things. The genetics class was the first time I was introduced to Punnett squares and the basics of genetics — a type of science education that I hadn't gotten at school to that point. I came back having learned a lot. It was also an introduction to living in dorms and being at a cafeteria, and that was exciting for me and also made me a lot more comfortable at subsequent camps and, ultimately, college.

You grew up in Auburn, AL. What were your experiences like going through school as a gifted student?

In my school system, there were not a lot of offerings for academically-inclined kids until tenth grade. I was bored a lot. One of the things I really enjoyed at SCATS was that learning was one of the purposes of being there, and the other campers were also curious. I enjoyed that type of engagement.

Was it a culture shock for you to go to school in the northeast?

It wasn't so much the northeast that was a culture shock — I had been looking forward to that. But in college, I did feel some envy toward students for whom the types of enrichment experiences that I had at SCATS were the rule rather than the exception. It’s part of why I remain so grateful for programs like SCATS: summer programs like the ones at WKU offered a special type of enrichment that can be especially hard to find in certain areas of the country.

Tell me a little bit about your professional path. You majored in applied math but also studied Chinese, and then you worked at The Center for Democracy and Technology, which protects online civil liberties and human rights. Then you went to law school, worked for the Department of Justice, and now work at Protect Democracy. How did you get from point to point?

It makes more sense than it may look like on paper! I studied applied math at Yale and the field didn’t play to my strengths. But I stuck with it — I’m stubborn like that — and ended up doing some computer science work as well. Through that work, I had the chance to spend time at Microsoft Research in Beijing over one summer. Yale had a good Chinese language program, so I then decided to use the opportunity to learn Chinese and, following graduation, I was able to study Mandarin in China on a Richard U. Light Fellowship.

When I was there studying Chinese, I spent a lot of time thinking about access to information because so many of the websites I liked to use were blocked. I started learning about China’s censorship mechanism. I discovered there was this whole field of tech policy that I hadn't known existed, and I was really interested in it — how government regulation affects the availability of information and our ability to self-govern. That's how I landed at the Center for Democracy and Technology. I loved my job — I was around a lot of awesome lawyers whom I really respected and who were working to make the world a better place, and so I decided to go to law school.

In August of 2016, after law school and clerking, I joined the Office of Legal Counsel in the Department of Justice, where the theme of how our democracy handles technology is very much present in some of the office’s work. Soon, though, a lot changed there — and I left in November 2018. I decided that what I felt was most useful was to go work on some of these rule-of-law and democracy issues that I'm working on at Protect Democracy.

Tell me what you see your role to be at Protect Democracy and what you hope you can accomplish.

The organization's mission is to keep our government from declining into a more authoritarian form of government. What I love about the organization — it's only two years old — is the integrated advocacy approach. We are kind of a Swiss Army knife of an organization. We do litigation to protect rule of law values, but we're also up on Capitol Hill lobbying, we're talking to candidates for office, we're writing op-eds, and we’re engaging with media, on the theory that change is difficult to make, so to make any change, you have to use all levers available. I'm doing a little bit of all-of-the-above, and it's an opportunity to be creative and not be limited to one tactic or one set of tools. It’s fulfilling.

Fall 2019

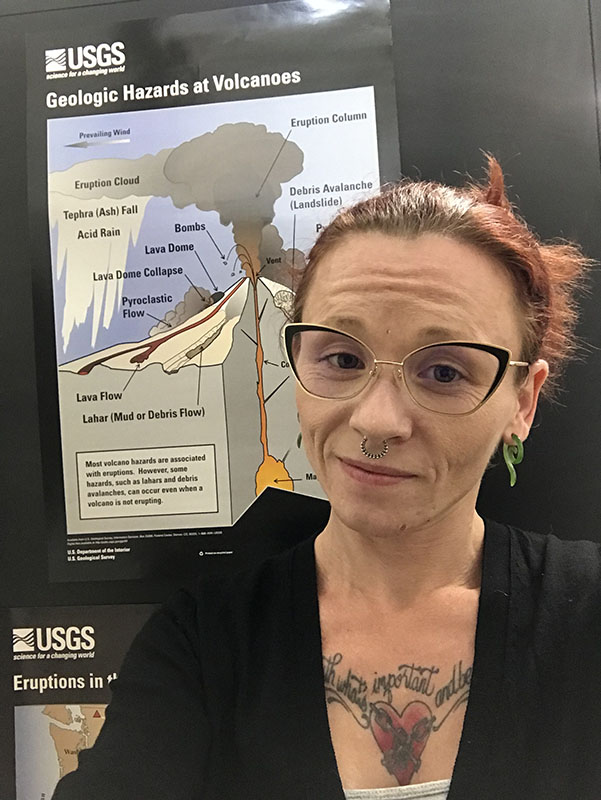

Spotlight on: Melissa Scruggs (VAMPY 1998-2001)

by Erika Solberg

Melissa Scruggs has achieved the dream of many a science-minded gifted student: she studies volcanoes. A Ph.D. candidate in geology with an emphasis on magma dynamics and petrochemistry at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) where she is part of the Magma Dynamics Group at the UCSB Department of Earth Sciences. She has published in American Mineralogist and the Encyclopedia of Geochemistry, and presented at the Goldschmidt International Conference in Geochemistry and the American Geophysical Union’s Annual Fall Meeting. She received an MS in geology with an emphasis on volcanology from California State University, Fresno, and a BS in geology from University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Melissa also achieved internet fame last January, when she tweeted (as @VolcanoDoc) about exacting revenge on her hard-partying neighbors who rolled “a giant sandstone boulder” in front of her car. The young men had overlooked the fact the she was “a tiny #geologist who has access to a VERY loud auto-chipper at 7:30 am,” and Melissa posted four pictures of her dismantling the rock in a most effective and noisy fashion. The post went viral, receiving 53.5 thousand likes.

We spoke with Melissa this fall about her time at VAMPY, her path to becoming a volcanologist, and how her lifelong curiosity occasionally allows her to destroy stuff in the name of science.

What was school was like for you as a kid?

I was really bored and frustrated. I went to Lincoln College Prep in Kansas City, Missouri, for middle school. It's one of the best schools in the state — the base classes are AP, and upper classes are IB — and I was still just bored. Everything was easy, and I hated it.

What do you remember about VAMPY?

I remember VAMPY quite vividly. I loved it. VAMPY felt more like a family than my family. I still talk to some of the people that I met my first year. They’re some of my best friends, and even though they live across the country, we send each other Christmas cards, talk, and Skype.

I took Physics my first year. I thought it was the coolest thing ever. I struggled a bit with the math because math is hard for me, but I loved being able to drop stuff off the top of the building. That seems to be a recurring theme for me — I like when I get to drop things off the tops of buildings or blow things up. VAMPY contributed to me realizing that being a scientist was a thing. I had watched Bill Nye the Science Guy and Beakman's World, but they were on TV — I never thought that that could be real.

Later I took Genetics, Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, and Medieval Literature. Whatever I happened to be into at the time, I obsessed over it. My dad says I'd do that even as a little kid — I'd find whatever I was interested in and never stop until I could get to the bottom of things. They found it incredibly annoying — VAMPY was their solution because they got rid of me for a month!

How did your academic interests progress?

I started getting into science in about fourth or fifth grade. In high school, I took chemistry. I had a great teacher, and she was so excited about it — her personality really drew me to that class. I took chemistry for two and a half years.

I didn't initially graduate high school — I dropped out when I was a senior because I was pregnant. I also still hated school — I showed up to take tests and made As on them, but on report cards I had Fs because of my attendance. I got my GED and worked as a legal secretary. I liked law, so I decided to be a paralegal. I worked full time during the day and went to school part time at night, and I got my Associate degree in paralegal studies.

Then I transferred to the University of Missouri–Kansas City. I thought science was really cool, but I wanted to be a lawyer, so I wanted to combine the two. There was an environmental studies degree in the Department of Urban and Environmental Geosciences. It had a lot of policy-oriented classes, so I decided to major in environmental science and minor in the pre-law track. I would get to do law, but I would get to enjoy science at the same time.

The major required taking environmental science and a couple geology classes. Then I took mineralogy, and they got me with the shiny minerals. That did it: I decided to change to geology. I took a class called the Archeology of Ancient Disasters. The archeologist who taught it, Dr. L. Mark Raab, passed away just this summer — he was really cool. He actually did his PhD dissertation on the Channel Islands offshore here in Santa Barbara, so it's a weird, full circle sort of thing.

The course was cross-listed in geology and classics and was taught by Dr. Raab and by Dr. Tina Niemi, a sedimentologist. The course was awesome because we got to see how geologic events affected the course of human history — like the 1755 earthquake in Lisbon. Most of the churches were destroyed, but the red light district fared fairly well. It was because of the underlying lithology (what rock type is underneath the ground) and how there were different rock types within the city — but people in the area started to question religion — why would God destroy these churches while the red light districts survived? Topics like that got me interested in natural hazards. And like I said before, I always liked throwing things off of buildings

I decided that I wanted to be a volcanologist when Dr. Raab showed a video of a volcanologist in a silver suit next to a lava lake. I said, “How do I get to do that?” They told me I had to get a PhD in volcanology.

What have you researched in your graduate studies?

For my master's degree, I worked on a volcano called Chaos Crags in Lassen Peak, in Northern California. I collected rock samples, crushed them up, melted them — fused them into glass — and then popped them in an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer, which measures the chemical composition of the rock as a whole. I also measured the chemistry of the individual minerals in the rock, so I could compare the two. From that information, I reconstructed the pressures and temperatures (P-T) that the different minerals in the magma crystallized at, before the volcano erupted. From those P-T estimates, I realized that after two different types of magma had mixed, there had to have been ~200 °C of cooling before the volcano erupted. Ultimately, if it wasn't for magma mixing, the eruption wouldn't have happened, but it probably didn’t happen right away.

Why are those findings significant?

The whole point of volcanology in my view is to try to mitigate as many disasters as possible. There's no way to predict a volcanic eruption at all — even a single volcano can have a completely different behavior from one eruption to the next — so by reconstructing what happens before an eruption, you can gain a better understanding of that volcano's behaviors. At Chaos Crags, the initial eruption was very explosive, then it lost some gas, and then it had some lava dome growth. Then it had another explosive eruption, and the rest of it was more lava dome growth. By looking at the differences between the individual eruptions, we can recreate what happened. It doesn't help to forecast future eruptions, but it does help to better understand the past behavior of a volcano.

Part of my PhD builds on my master's work. I have additional geochemistry data. Instead of looking at the minerals in the rocks, I looked at the isotopic signature of the rocks as a whole. I was able to find evidence that as the magma comes up from depth into the base of the chamber to mix with the magma that's already there, it's incorporating some of the upper crustal rock around it as it travels upwards.

The other part of my PhD is looking at the Pu`u `O`o eruption at Kilauea on the island of Hawai’i. I use a computer program called the Magma Chamber Simulator — you can look it up at https://mcs.geol.ucsb.edu/. It's a thermodynamically-based (energy- and mass-constrained phase equilibria modeling) computer program that can model what the chemistry of the rocks should look like if certain processes were to happen. I take the actual chemistry of the lava that has erupted and say, “Okay, I know that this is what came out. Now what had to happen underneath the ground in order to get there?” and that's what I model. It takes a long time because I have to model all these different scenarios, and the natural earth has a ton of variables.

I'm working on the Episode 54 eruption, which was in 1997. It was a 23-hour long eruption that occurred just a few months after GPS was first installed in the Pu`u `O`o cone. With GPS, you can calculate the volume of magma that's moved. From using the volumes of magma, where they were located, and the chemistry of the lava that was erupted at the time of the eruption, I was able to figure out that the magma that came in to the system mixed with a pod of leftover magma that was pretty crystalline and had evolved quite a bit. I was able to figure out the composition of that magma, its crystallinity, and its conditions and approximate volume before Episode 54 occurred.

What are your professional goals at this point?

I have officially advanced to PhD candidacy. I’m hoping to defend by the end of the summer. I was selected for the American Geophysical Union conference in December — it's the biggest international geology conference — so I’ll present part of my PhD work there. I really would like to research.

And you've been doing all this as a parent as well?

Yes. My daughter is 16 — she's a great kid. She started taking chemistry this year, and she came home and said, “Mom, I really like chemistry!” and I said, “It's really cool, huh?”

Any final thoughts on VAMPY? Has it had an impact on your life?

Without a doubt. My mom remembers me telling her I liked it better than school because there were people there who were like me. Even though I got to go to a school where the classes were demanding and the people were nice, I still didn't feel I fit in. VAMPY gave me a place to look forward to going to. 24 years later I still talk to some of my friends from camp on a weekly basis. Those are my homies.

My first year — this is how I got roped into this group of friends — there was this rule that we weren't allowed to take the elevators. But there was this thing called the Elevator Record. We crammed 43 people into a 17-person capacity elevator. We went up three feet and got stuck for four hours. We did not make it to class on time.

Things like the dances, mandatory fun, and meeting people from everywhere who were just as into things as I was all helped me so much as a person. VAMPY was such a great experience, and it has really helped me to grow into who I am today.

Summer 2019

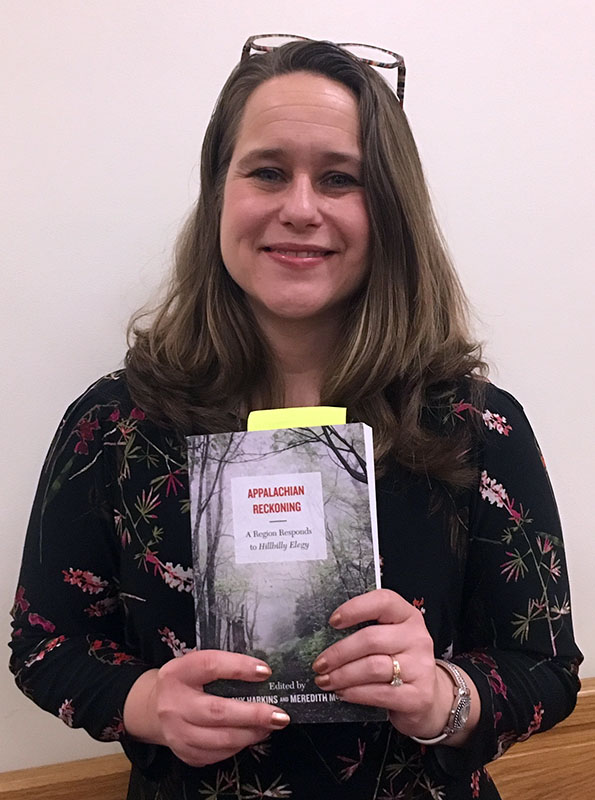

Spotlight on: Dr. Kirstin Hamblin Squint

(VAMPY 1986-89)

by Erika Solberg

Kirstin is an Associate Professor of English at High Point University in High Point, NC. She received her BA in English from Eureka College in 1995, her MA in English with a fiction writing emphasis from Miami University of Ohio in 1998, and her PhD in comparative literature from Louisiana State University in 2008.

Her published works include the 2018 monograph LeAnne Howe at the Intersections of Southern and Native American Literature and the forthcoming Swamp Souths: Literary and Cultural Ecologies, co-edited with Eric Gary Anderson, Taylor Hagood, and Anthony Wilson. Her essay “Kentucky Coming and Going” appeared as a chapter in the 2019 Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy, edited by Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll. In 2019-20 she will serve as the the Whichard Visiting Distinguished Professor at East Carolina University,

What was VAMPY like for you?

The first year, I took an expository writing class, and for much of my life my goal

has been to be a writer, so that class alone was really helpful. It was the first

time I read Faulkner. I wrote a piece about my grandmother, and we did peer reviews

with our classmates. I had never had any kind of formal writing training — that class

was very powerful for me. I took other interesting classes, but that one was life-changing

because of who I am intellectually.

The other thing was that I came from a very poor rural community in Kentucky, neither of my parents went to college, and no one I knew in my family had gone to college. I was meeting children of lawyers and college professors and people who were going to magnet schools in Louisville — people from socio-economic and educational backgrounds that were so different from mine. By becoming friends with those people and realizing the way that I had felt different from my classmates and my community, I didn't feel so isolated anymore.

At what point did you decide you wanted to go to graduate school?

I knew that pretty early on — I remember in seventh or eighth grade, I had this idea

I was going to get a PhD, and I thought I was going to do it at Harvard or something

— I had no idea. But that's the thing — I met people at VAMPY whose parents had gone

to Harvard and who did themselves go to Harvard, so suddenly that was within reach

to me, and it was not within reach previously. Again, VAMPY exposed me to a world

that I had never been in contact with before.

I discovered as an undergrad that I wanted to be a a fiction writer, so I got into the MA program in English at Miami of Ohio. I wound up moving out to New Mexico and taught in a high school on the Navajo reservation for a year. I learned that I didn't want to be a high school teacher, but I learned that I did love teaching. After I finished my master’s, I started doing community college teaching, and I liked it because I had a lot of first generation students like me. It was work that was meaningful.

How did your research interests develop in graduate school and afterwards?

What really started my research was teaching on the reservation. It opened up my world

in terms of seeing and understanding settler colonialism and the relationship of indigenous

people to the United States government. I had a growing interest in native writers,

and when I was at the community college in Flagstaff, AZ, I created its first Native

American literature class. There was a really high number of Native American students

who attended, a lot of of Hopi and Navajo students, so that felt like a really important

thing to do.

I read Choctaw writer LeAnne Howe’s novel Shell Shaker when I was at LSU. That book moves between the 18th and 20th century in the Choctaw homelands of what became Mississippi, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. I realized when I read it that I could look around Louisiana, and all these places had Choctaw names, like Bogue Chitto and Atchafalaya. It made me think simultaneously about native presence and absence in the southeast.

I wrote a dissertation on 20th and 21st-century Native American writers, called Native Spiritualities as Resistance: Disrupting Colonialism in the Americas. As I was thinking about what my next project would be, I thought about what I had enjoyed the most about the dissertation. I had done an interview with LeAnne Howe in 2008, and it became my first national publication. I thought, “I really want to write more about her” and then realized I wanted to write a book about her — nobody had written one yet. LeAnne Howe at the Intersections of Southern and Native American Literature came out from LSU Press in 2018.

I'm under contract for another book about her — it's an edited collection of essays with the University Press of Mississippi. I also coedited a forthcoming collection called Swamp South: Literary and Cultural Equalities. A lot of things have happened in the last couple of years, and it's been super exciting.

What is it like being someone who is not Native American working in native literary

studies?

Having had the experience of living on a reservation, I have an awareness of settler

colonialism that a lot of Americans don't have. I'm always aware of my outsiderness,

and I try to keep learning from the native scholars I know and whenever I'm in a native

community. I never think that I know as much as I can know — I'm always learning and

trying to figure out the best way to be an ally.

For example, I just wrote a letter of recommendation for one of my students who is Eastern Band of Cherokee. She's going to do a community health certificate program at Western Carolina because she wants to synthesize western medicine and native healing methodologies and wants to go on to graduate school. I'm so proud of her, and I feel like anytime I have an opportunity to mentor native students, I want to do that.

It sounds like you're leveraging power from your position to help people who don't

have that access, which relates back to when you were younger and you didn't have

access to certain things.

You're right. I taught on the reservation and at Southern University, an HCBU in Baton

Rouge, but I didn't understand this until recently. The piece that I wrote for Appalachian

Reckoning was about my family in dysfunctionality, how my grandparents came out of

the mountains in southeastern Kentucky and their shame about their hillbilly identity.

They carried that shame with them and passed it on — we weren't allowed to listen

to banjo music because there was this real shame attached to it — “we don't want anybody

to think we're hillbillies” — but of course, they couldn't see the extent to which

they embodied that anyway. I went to school out of state because I wanted to get away

from Kentucky. I had all this shame.

When I was on a panel at the Appalachian Studies Conference in March talking about Appalachian Reckoning, someone asked about Appalachian identity and double consciousness, and it hit me so hard. I've talked about the idea of W.E.B. DuBois’s double consciousness with other ethnic minority communities and when I've taught multiethnic literature, but it never occurred to me that I might also be carrying a form of double consciousness from a hillbilly perspective. For all of my life, I couldn't see the forest for the trees, why I was drawn to these places doing these things. The Appalachian Reckoning piece has been a big moment of me coming to some awareness about my life.

Anything else you want to say about VAMPY?

VAMPY was a transformational experience. It opened up the world in so many ways. It's

hard to measure the impact that it had on me.

Fall 2018

Spotlight on: Karyn Andrews (SCATS 1986-87)

by Erika Solberg

Karyn is currently in the WKU graduate program in gifted studies, working toward her endorsement. For her practicum, she taught a course at SCATS this the summer.

Where did you grow up?

In LaRue county, in a little town called Buffalo.

How did you find out about SCATS?

My mother was working on her gifted endorsement at the time — she actually taught

at SCATS my first year. I took her class — a newspaper class.

What other memories do you have of SCATS?

Going to Opryland — that was fun. I remember making a camera out of an oatmeal box and getting to develop the pictures. There is a drawing that I did in a drawing class still hanging on the wall of my parents’

house.

What career have you pursued?

I work at Mt. Washington Elementary in Bullitt County as the school librarian. I taught

band for two years at a Christian school and then want back to graduate school and

got my Masters in library. I’m now doing the gifted endorsement toward earning Rank

1 as a teacher.

Why did you decide to do the gifted and talented endorsement?

It’s something I've always wanted to do. I’ve always been a strong advocate for gifted

education.

Have there been topics you have covered in your graduate work that have made you reflect

back on yourself as a gifted student?

Definitely. I've learned a lot about myself. I didn’t realize that getting frustrated

easily and being very emotional were often tied in with being gifted. I would get irritated with teachers who wanted me to work a problem the way they wanted

me to work it out rather than the way I wanted to work it out.

What was it like growing up as a gifted young person?

I was lucky my parents were advocates for me. Once she realized I knew all my letters when I was 19 months old, my mom thought,

“Hey, this isn’t normal. We need to figure something out.” She brought me to Western

when I was four and had me tested. I was lucky in that I had teachers who challenged

me up through third grade. There was no gifted program in my school until I was older,

and that was a pull-out, one hour, one day a week program. The superintendent in the

district now does a good job with middle and high school students, but with elementary,

we’re still getting there.

Has there been any part of the graduate program that you have particularly enjoyed?

I've enjoyed all of it. I’m really enjoying SCATS. This is my first time working with

middle school kids, except for when I did student teaching years and years ago, and

it has not been as scary as I thought it would be!

Your class is called Book, Books, Books. What are your specific goals?

I want students to have shared with each other books and book series. I want them

to come away with a big, long list of new books to read and an appreciation for different

genres. Their interests are guiding the direction I take in class. I think it’s working!