WKU History - Featured Image

A portrait of nine African American women at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), Georgia, taken in 1899 or 1900. Founded in 1865, Atlanta University was among the first Black universities and colleges to accept women, and built a women’s dormitory in 1869; however, only one woman earned a bachelor’s degree there between 1876 and 1895, although this number rose to seven between 1895 and 1900. This photograph, by Thomas Askew, was displayed at the 1900 Paris Exposition, as a part of “The Exhibit of American Negroes,” curated by W.E.B. Du Bois, Thomas Calloway, and Daniel Murray. (Library of Congress Collection)

Previous featured images

Black students being escorted by Louisville and Kentucky State police at the end of the

school day, September 8, 1975. Court-ordered busing between Louisville city schools and

predominantly White suburban schools began on September 4, to counter the de facto

segregation of schools within Jefferson County. The program was met with widespread

protests by White families opposed to busing, as well as violence against Black students; Louisville's

mayor called in the Kentucky National Guard on September 6 in response to rioting,

and armed guards began riding with students beginning September 8. While anti-busing

protests continued up to the Democratic Convention in Louisville in November, the

program continued and general opposition to school integration measures eventually

began to decline. After a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision that race could not be

the primary factor in assigning students to schools, district officials had to design

alternative plans to foster racial and socioeconomic integration across schools in

the Louisville area. (Photo by Keith Williams, The Courier-Journal)

Source • More info

African American sports stars surround boxer Muhammad Ali in Cleveland as he defends

his refusal to be inducted into the armed forces during the Vietnam War on June 4,

1967. Ali’s rejection of the draft, along with his earlier embrace of the Nation of

Islam, was unpopular among white and Black Americans alike; many reporters refused

to use his Muslim name. Fellow athletes tried to convince Ali to agree to participate

in exhibitions for US troops in exchange for being allowed to continue boxing professionally.

However, Ali would not back down from his stated position: “Why should they ask me

to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown

people in Vietnam after so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs

and denied simple human rights?” The athletes supported him, but an all-white jury

ruled he had illegally evaded the draft, and he was fined and banned from boxing until

the US Supreme Court overturned his case in 1971. (Photo by Robert Abbott Sengstacke,

Getty Images)

Front, left to right: Bill Russell, Ali, Jim Brown, and Lew Alcindor (later Kareem

Abdul-Jabbar). Behind: Carl Stokes (months later Mayor of Cleveland), Walter Beach,

Bobby Mitchell, Sid Williams, Curtis McClinton, Willie Davis, Jim Shorter, and John

Wooten.

Source • More info

Shirley Chisholm on November 5, 1968, after winning the election for New York's 12th Congressional District and becoming the first Black woman to join the U.S. House of Representatives. Chisholm, who earned a degree in education, and had previously been a nursery school teacher and director as well as a member of several political organizations in Brooklyn, served as a New York State legislator between 1965 and 1968. Chisholm's 1968 campaign emphasized her connection to her district, and tactics like driving through local streets with a loudspeaker or speaking Spanish with prospective constituents led her to a 2-to-1 victory. She was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Women's Political Caucus in 1971, and the National Congress of Black Women in 1984. Chisholm also ran for president of the United States in 1972. She retired from Congress in 1983, though she remained politically active; after her death in 2005, Shirley Chisholm was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 (Pictorial Parade/Getty Images Photo).

Marsha P. Johnson protesting with the Gay Liberation Front in front of New York City Hall following the Stonewall riots in the summer of 1969. The riots, a series of violent confrontations with police that began in response to a raid on the Stonewall Inn in June 1969 (and to years of discrimination beforehand), were a landmark moment for LGBTQ rights in the United States. Johnson was among those resisting police at Stonewall, and a key figure in the gay rights movement it helped generate. The Gay Liberation Front, formed a month later, organized marches and protests to continue the momentum from Stonewall, and led to related groups like the Lavender Menace (a lesbian activist organization) and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), founded by Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, a close friend. Although Marsha P. Johnson struggled for much of her life with poverty, homelessness, and mental illness, she remained active in the fight for gay (and trans, though the term wasn't commonly used then) rights up until her death in 1992. (Associated Press Photo)

African-American voters line up to vote in the Democratic primary election in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 3, 1966. This election was the first major one after the 1965 Voting Rights Act took effect. The Act, aimed at ending widespread disenfranchisement of Black voters, had been passed in August 1965, following a long campaign of civil rights protests; in particular, the spectacle of "Bloody Sunday" on March 7, when participants in a protest march were assaulted by state troopers as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, was instrumental in moving President Lyndon Johnson and Congress to action. (Associated Press Photo)

Juanita Abernathy, Ralph Abernathy, Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King Jr., Floyd McKissick, and Claude Sterrett participating in the March Against Fear, 1966. On June 5, James Meredith set off on a solo march from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, both to protest continuing racism and to encourage voter registration among African-Americans. Although Meredith had intended not to make it a major media event, after he was wounded by a white gunman on the second day, civil rights organizations (including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality) traveled to Mississippi en masse to continue the march, with some 15,000 people – including a recovering Meredith – entering Jackson on June 26. (Photo credit Bob Fitch)

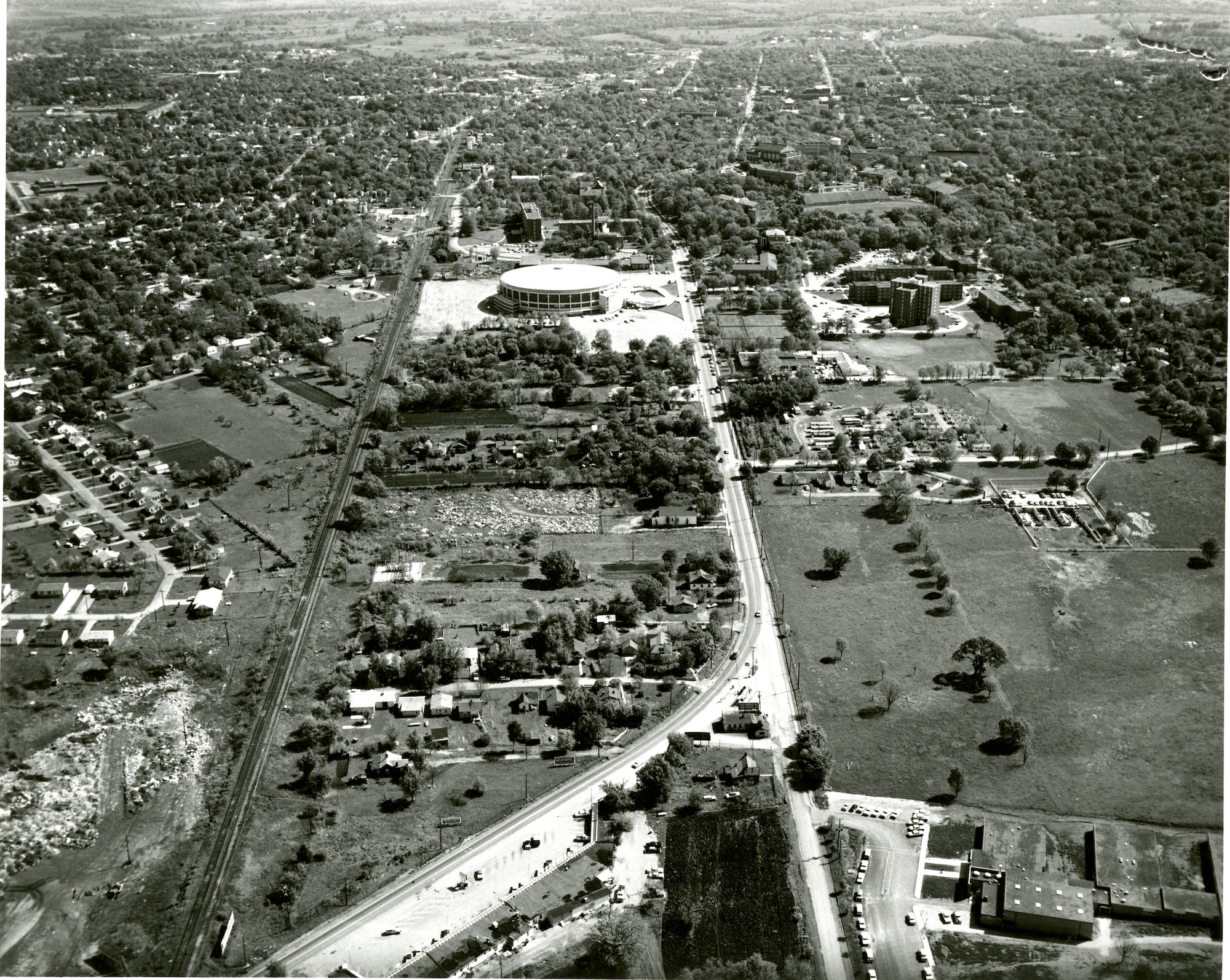

In 1964, WKU began the demolition of Jonesville, a black village encompassing about thirty acres and located on the western border of its campus. Jonesville was home to many of Bowling Green’s black professionals including schoolteachers, doctors, dentists, and ministers. In addition, the community also was comprised of numerous businesses including a funeral home, gas station, restaurant, grocery store and boarding house. Wanting to expand its campus, the University did not have the financial resources to purchase the properties at fair market value and thus took advantage of urban renewal policies to condemn the homes for arbitrary infractions such as unsatisfactory standards of maintenance or not meeting minimum yard setting requirements. Jonesville’s residents vigorously resisted this initiative, as it was readily apparent to them that the reason for choosing the Jonesville corridor had more to do with race than other considerations. WKU’s urban renewal project succeeded but, in the process, destroyed black proprietorship in Jonesville and induced many residents to relocate to north Bowling Green or to public housing in the Delafield area. (Caption by Selena Sanderfer and Alexander Olson; photo credit WKU Archives)

Suffragettes celebrating the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Following almost a century of protest, women gained the right to vote with the 19th amendment, which was passed by the U.S. Senate in June 1919 and (narrowly) ratified by three-fourths of the states the following summer. Some 8 million women voted in the November 1920 elections, although women of color continued to face a variety of obstacles to exercising their right to vote, from poll taxes and local restrictions to intimidation and violence, for many decades to come. (Photo credit Bettman Archives/Getty Images)

Ella Baker (center) and Myles Horton (left) at the Highlander Folk School, 1960. Baker, who trained in civil disobedience strategies at the school, was a staunch advocate of grassroots activism rather than hierarchal leadership, partly due to her previous experiences working with the NAACP and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She would be a key mentor for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the 1960s. Horton, a native Tennessean, founded the school in 1932; after it began to focus on civil rights during the 1950s, the school's charter was revoked by the state in 1961 in apparent retaliation for this work, though it was reincorporated later that year as the Highlander Research and Education Center. (Photographer unknown/image from Highlander Research and Education Center)

Vivian Malone and James Hood holding a press conference after registering for classes at the University of Alabama in June 1963. The university was required to admit Malone and Hood following an NAACP lawsuit over the Supreme Court's 1954 school desegregation decision. Earlier that day Alabama Governor George Wallace sought to block entry to the campus, and was only removed when the National Guard was called in. (Another African American student, Autherine Lucy, enrolled in 1956 but was expelled over mob violence against her attendance.) Malone became the first African American student to graduate from the University of Alabama; Hood left two months after enrolling but returned to earn a Ph.D. in 1995. (Associated Press Photo)