What Happened to Jonesville?

In the summer of 2022, seven Southcentral Kentucky residents explored the history and story of Jonesville through the Community Scholars program, a statewide training program for documenting traditional arts adn culture. Guided by the Kentucky Folklife Program and Kentucky Arts Council, this group of researchers explored how to conduct fieldwork research, then applied their training to conduct oral history interviews with former residents of Jonesville and their descendants, creating this interpretive exhibit.

"I would take you back in time, if I could do it. I would let you have the Jonesville experience. My grandchildren...at 14, 15, they're not really sick of hearing my stories. They say, 'We want to hear you tell some more."

- Connie Gatewood Jones

Connie, Rachel Jackson, and Maxine Hines Taylor outside of Rachel's house. Date unknown.

Jonesville was a vibrant, prosperous African American community in Bowling Green. The earliest land deed dates to 1881, but the community likely began earlier. At its height, Jonesville had 85 houses and was home to many families who worked, attended school, and worshipped at church, and lived as a community.

"We had no keys to houses. We didn't have to lock up cars. It was a very respectable neighborhood, and people respected you."

- Rev. Porter W. Bailey

In 1963, the City of Bowling Green directed a campaign of "urban renewal" that demolished Jonesville and removed its people. The land was sold to WKU. Although the buildings are gone and many residents have passed on, Jonesville's stories live on through former residents and their descendants.

On the Map

Jonesville was about 30 acres, bordered by Russellville Road (68/80), Dogwood Drive, and the railroad tracks, although oral traditions spread it beyond those boundaries. This area is now occupied by WKU's softball and soccer fields up to Diddle Arena, the water tower, and over to Graves Gilbert Clinic. The map below was created in 1963, when urban renewal began. Many names on the original map were misspelled, which suggests a lack of care for the residents. We have corrected misspellings based on local knowledge. Properties acquired further northeast and east of those shown here were acquired as early as 1957 by purchase or condemnation suits. The shadows indicate approximate locations of roads and WKU athletics faciltiies in 2022.

Other maps of Jonesville around the time of its demolition can be found at the following links:

- UA3/3/1 - Oversize map showing properties to be acquired through urban renewal, Paper 2150.

- UA3/3/1 - Oversize map showing proposed location so fnew WKU facilities on Jonesville properties, Paper 2148.

- UA3/3/1 - General area map of Jonesville dated 1963, Paper 2147.

Families

Jonesville was comprised of tightly-knit families that formed a community. While this list is not complete, here are many of the families who lived and worked in Jonesville.

E. Alexander

M. Alexander

Alma

Austin

Baker

Bailey

Blewett

Bradley

Buford

Butts

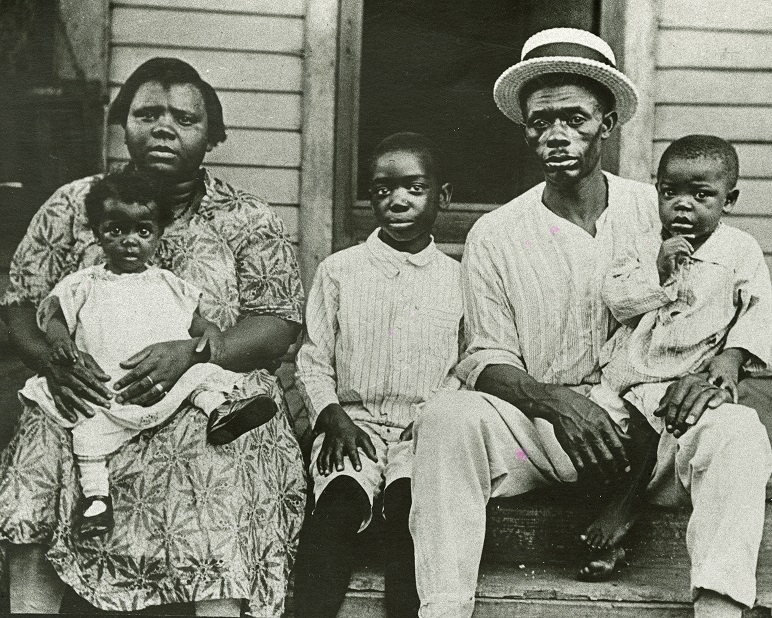

Alene Doyle (mother), Verlie, Ferrell, William James, Will (father), and Henriette Taylor.

Caldwell

Dover

Edison

Ennis

Freeman

Hadin

Hartsel

Holson

Lightfoot

Lovett

James Sr., Gladys, James Jr., and Nancy Bailey.

James Sr., Gladys, James Jr., and Nancy Bailey.

Potter

Ragland

Ray

Sanders

Sweatt

Taylor

Walton

Woods

Schools

Education was important to the community. Children attended segregated schools.

"Our parents and grandparents and all were smart enough to know that knowledge is power and we would need that knowledge to survive in the world today." - Maxine Ray

Jonesville Elementary was the only school located in the community, but it closed in the early 20th century. Students then attended H.D. Carpenter/Delafield Elementary School, a Rosenwald School that had two classrooms with grades 1-4 on one side and grades 4-8 on the other. The cafeteria served as a third classroom and the library. Staff included Principal Clara Cole, teachers Mrs. E.T. Dorsey and Mrs. Hutchinson, and caretaker Mr. Kirby, who lit two wood-burning stoves every morning to warm the building.

James Bailey Jr. and Nancy Bailey, graduation from Delafield Elementary.

James Bailey Jr. and Nancy Bailey, graduation from Delafield Elementary.

High Street High School Band.

High Street High School Band.

Bowling Green Academy was a Presbyterian boarding school at the corner of 3rd and State Streets, attended by African American students from Jonesville and surrounding counties. Many worked for white families in exchange for tuition, room, and board, often in the early morning or evenings as servers, cookes, and cleaners.

State Street High School was the primary high school for Jonesville students and boasted successful basketball, football, and track teams. It was later replaced by High Street High School.

Businesses and Professions

Jonesville residnets were largely self-reliant. Residents owned an array of local businesses, including some that operated out of their homes.

Hardin's Roadhouse, opened by Bill and Masie Hardin and continue by their son, Will, was famous for its BBQ sandwiches. Taylor Sanitation, a waste collection company still in operation today, began with Dan Taylor picking up food scraps to feed the family hogs. Other businesses included Henry Callaway's Fruit Stand, Blewett's Filling Station, Audrey Bailey's Beauty Shop, Stallard's Chicken butcher shop, Mae Wade's Restaurant, Loving's Barber Shop, Pryor's Clearners, and Edgehill Shopping Center, one of the first shopping centers in Bowling Green.

"I had a customer call me the other day, that had been a customer for 67 years, and they were talking about granddad. It's amazing. His character and the goodness that came out of Jonesville still carry." - Tina Taylor

Callaway's Fruit Stand.

Callaway's Fruit Stand.

Some residents became regionally known for their talents. Their stories live on in descendants' memories and newspaper records.

Audrey Bailey's Beauty Shop for women operated right out of the home of Porter and Audrey Bailey. She had many customers who would travel to the shop from as far away as Horse Cave, Ky, and Tennessee.

Residents received medical care from dentist Dr. W.S. Yarbrough, whose Jonesville home had hardwood floors and a spiral staircase. Family physician Dr. Zachariah Jones made house calls and practiced well into his 90s.

Stone masonry was a generational profession for many residents. Virgil Bailey worked on the masonry for the WKU President's office, the stone wall on Normal Street across from the Planetarium, and many buildings at Fisk University in Nashville. Working alongside other Jonesville residents, Bailey laid the foundations for houses throughout Bowling Green.

Leisure

Residents enjoyed each other's company at lawn parties, high school basketball games, and movie nights. People took great pride in their gardens, which included fruit and walnut trees, zinnias, sunflowers, diverse vegetables, and medicinal herbs. Every family had some kind of garden and people would share their bounty. Movie nights provided by grocery store owner Mr. Reeves and the Dr. Pepper Bottling Co. were held in the field across from Mt. Zion Baptist Church. Residents would bring blankets and lawn chairs to watch the movies. Many Jonesville residnets were talented musicians.

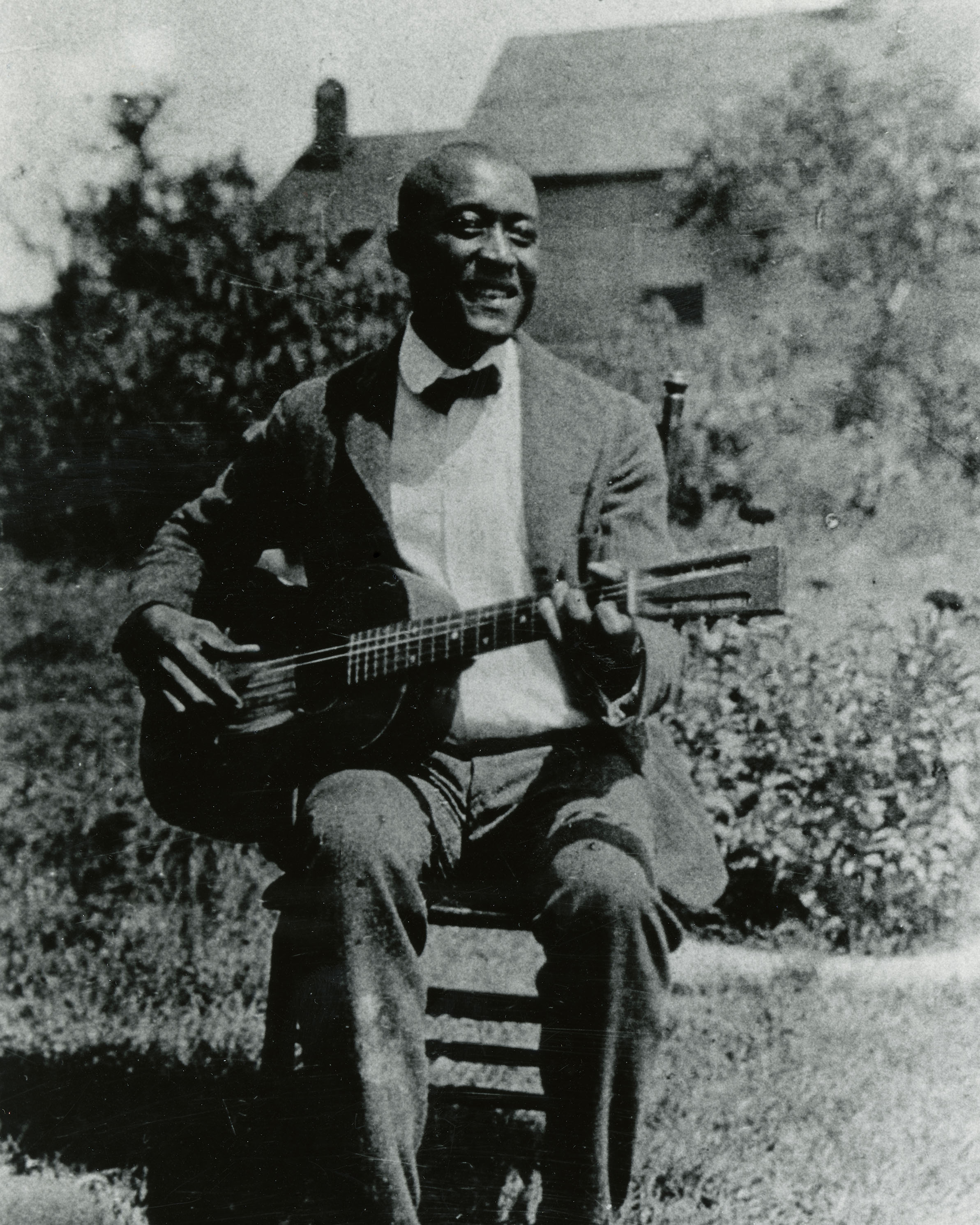

Harry Taylor, a musician who could play a variety of instruments. In an interview,

his niece, Angela Townsend, stated, "On a clear day, you could hear him all over Jonesville."

Harry Taylor, a musician who could play a variety of instruments. In an interview,

his niece, Angela Townsend, stated, "On a clear day, you could hear him all over Jonesville."

Marilyn Ellen, Corrine Bailey, Mary Austin, Hershel Austin Jr., James Bailey Jr., and Nancy Bailey relaxing outside Virgil Bailey's home.

Gonzela Simons, Will Simons, and Maggie Woodson in flower (left) and vegetable (forefront) gardens.

A Community Centered Around Church

"And we had everything at church because the church was the center of our extracurricular activities. [...] The church is where the ladies taught young girls how to be ladies. The men and the boys were taught the same: manners, how to treat a lady, how to hold a chair to seat her. There was a lot out back behind the church where we could play baseball. We had the weenie roasts and our pastor would tell us ghost stories on Halloween night, we would all be scared to death. We just learned life there. The church was everything to us." - Maxine Ray

Mt. Zion Baptist Church

Mt. Zion Baptist Church

Rev. Stewart and churchgoers talking after service.

Founded in 1886, Mount Zion Baptist Church was the main house of worship in Jonesville. The pastor was the moderator, a kind of leader, of the Union district representing 30 to 45 churches in the area. After Mt. Zion was razed, the congregation was allowed by WKU to meet at the place where it stood: Diddle Arena. Eventually, Mt. Zion was rebuilt at 175 Graham Drive.

AME Salters Chapel was another church located in Jonesville, but moved to 3rd and Park in the Shake Rag neighborhood before WKU sought to purchase Jonesville.

Urban Renewal Campaign

In the 1950s, WKU sought to expand campus after a postwar student population boom. The Board of Regents looked to Jonesville as their preferred place to expand. When private purchases were unsuccessful, they resorted to filing condemnation suits through the City of Bowling Green.

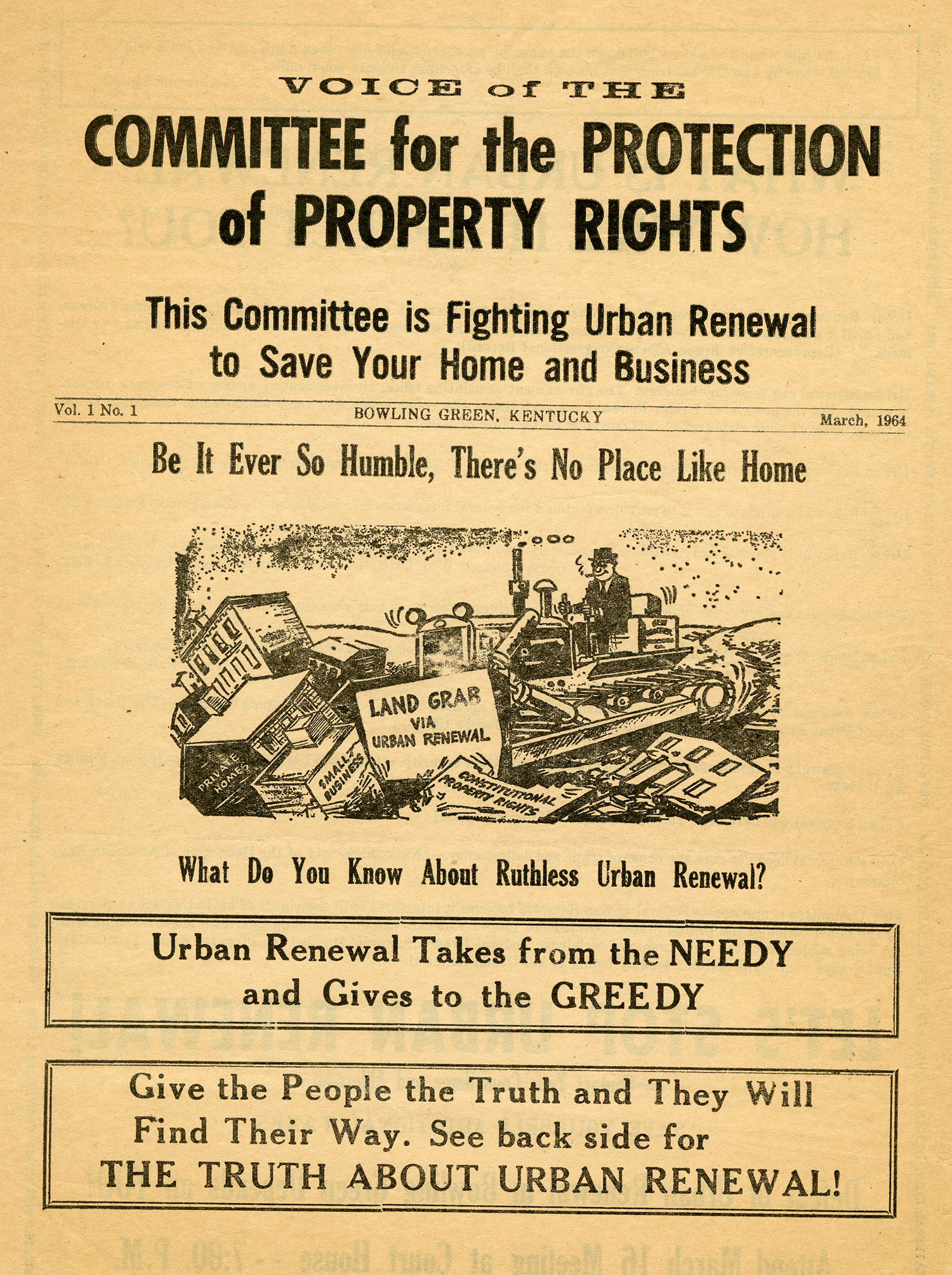

In 1963, the City took advantage of the Federal Renewal Program, infamous for rubber stamping urban renewal campaigns. In March 1964, Jonesville was declared an urban renewal area and the City received a $614,753 grant to carry out the project. The City moved forward wiht public hearings for the purchase and resale of Jonesville properies.

"My great grandparents were barely out of slavery when they were able to purchase, work, and maintain the land which WKU usurped though urban renewal at almost no compensation. I was very hurt to see them fraught with frustration and depressed about the prospect of losing what they had worked so hard to achieve." - Angela Townsend

Resistance

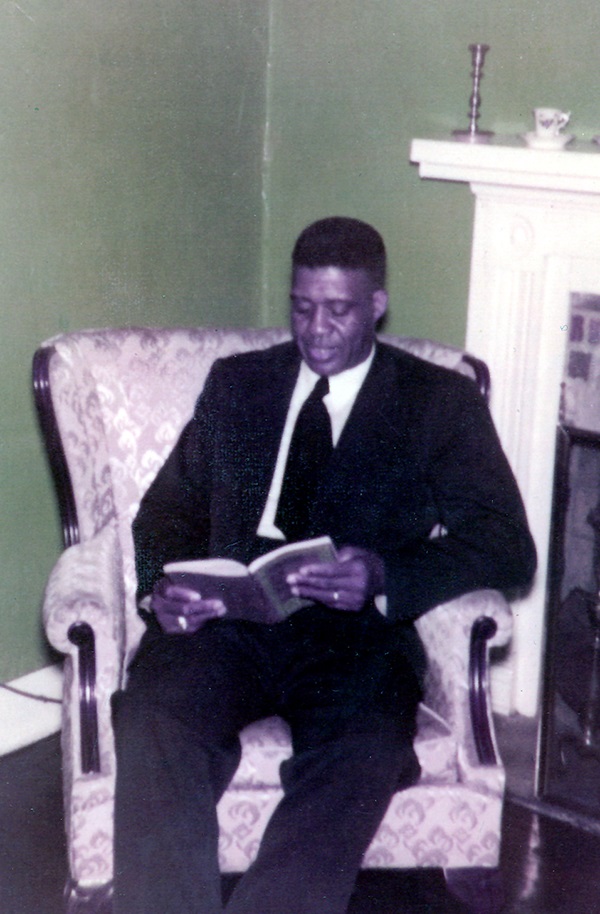

Residents of Jonesville did not willingly give up their property, and with it, their livelihood. They resisted by writing letters, protesting at meetings, and waiting as long as they could to move. The Committee for the Protection of Property Rights was formed to fight the decision. Aaron Overfelt was the committee's attorney and Rev. J. H. Taylor was the chairman. Rev. Taylor was a major force in organizing resistance and voicing opposition through letters to local newspapers. A petition was circulated throughout the city to rally support to stop the urban renewal project.

"They made known their intentions to buy our homes, whether we wanted to sell or not, and stated publicly that they have no intentions of paying us enough to buy or build without incurring indebtedness." - Rev. J. H. Taylor

Others made public appeals. White resident M.M. Blewett pointed out that the College had many old buildings in poor condition that could be replaced. At the City's final decision meeting, 300 Jonesville residents attended in overflow to protest the decision.

Rev. J.H. Taylor

Demolition

For a property to be approved for urban renewal, it must be deemed "blighted" - a vague defiinition. In the case of Jonesville, homes were deemed blighted for issues as minor as lacking sufficient off-street parking. On December 2, 1963, the City gave final approval for the project. Two months later, WKU declared its intentions to build sports stadiums and other facilites on the land. By 1967, the last building in Jonesville - Mt. Zion Baptist Church - was bought and razed. The church's destruction marked the end of Jonesville.

"Like most people say, 'negro removal,' that's what it boils down to and that was probably what was the theme. When you think about the whole process, it was just a system that was devised to take property from Black folks when they wanted it." - Alice Gatewood Waddell

Where Did People Go?

Residents had few options in segregated Bowling Green, many of which they considered a significant downgrade from their Jonesville homes. Some residents were eligible for low-interest, government loans up to $10,500. Bank loans, otherwise, were not an option due to racist lending practices. Those who had sold to WKU early in the 1960s received more than those who held onto their property longer. Yet nearly all Jonesville residents received less than their property's actual worth. Some were paid as little as $100. Their community was gone. and its demolition greatly impacted the intergenerational wealth among their families. Most had to start all over.

The Bailey Family

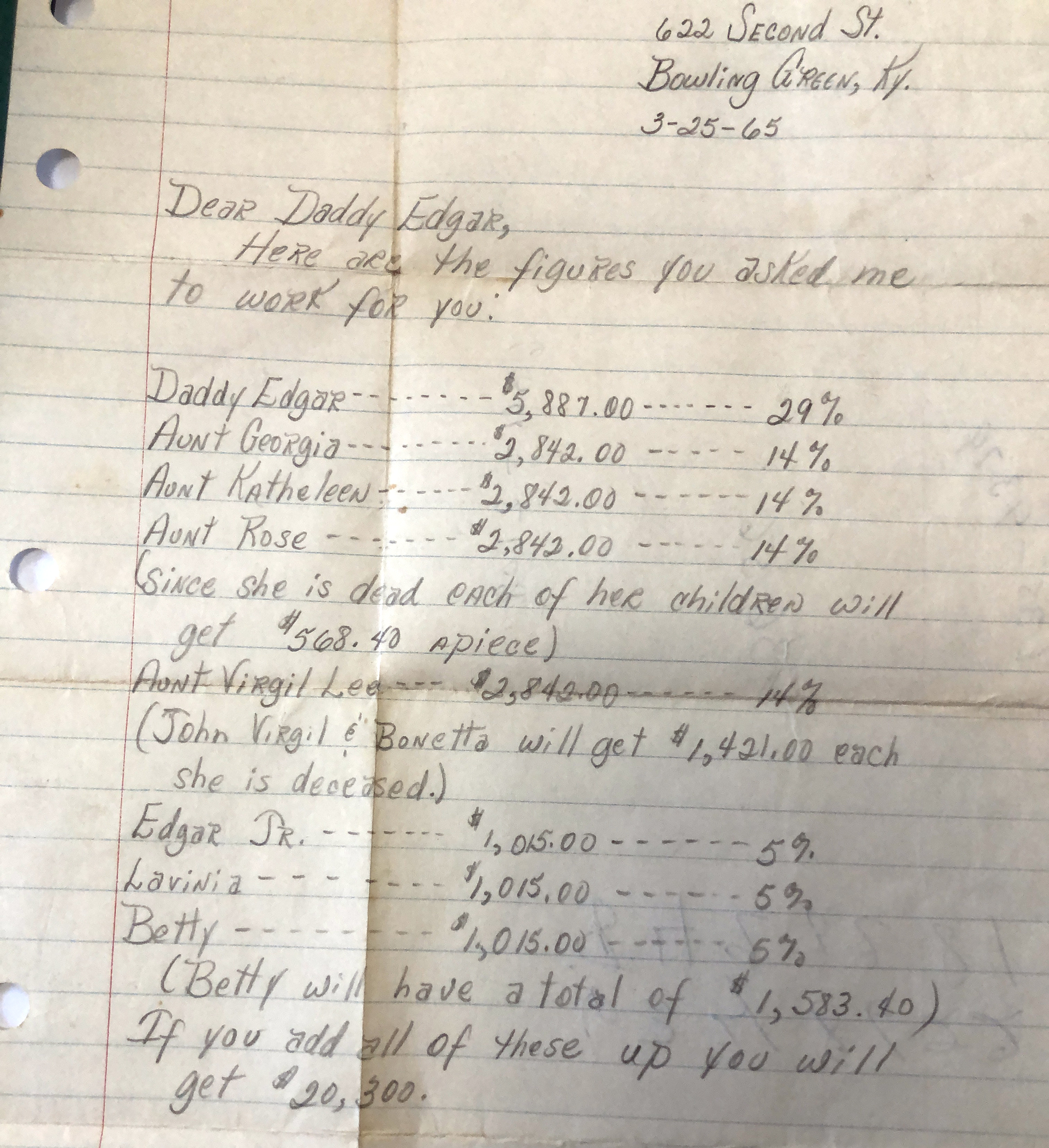

In 1965, 16-year-old Connie Gatewood Jones calculated each family member's portion from their property's sale. The property sold for $20,300. The profits were split among eight relatives, as shown in Connie's letter to Daddie Edgar (at right).

Call to Action

So where do we go from here? There is no way to bring back Jonesville, but maybe there is a path forward toward healing as a community and beginning to reconcile with this ugly part of history. Descendants of Jonesville have some ideas.

"Why don't we have a whole building dedicated to the Jonesville community with historical artifacts and history and all that and not something just tucked off in the corner, you know? Because tucked off in the corner is what we've been getting for years."

- Tremayne Taylor

"I do have hopes that it will make everybody aware of what happened. And when I say everybody, I mean everybody, the whole Bowling Green, the whole world."

- Wathetta Buford

"I hope that something can be done that will be tangible. Not just looking at a marker.... Something that will encourage people to not go backward. [...] Something big enough to make a statement that 'we're sorry, that that took place'...to make the descendants of those people have comfort and know that somebody cares."

- Alice Gatewood Waddell

In 2021, local artist and Jonesville descendant Alice Gatewood Waddell and WKU professor Mike Nichols collaborated on a buon fresco mural commemorating Jonesville. Three WKU students - Aisha Salifu, Cecilia Morris, and Riley O'Loane - worked alongside the artists to make the vision come to life.

The technique used – fresco painting – is notable for its permanence. Used through history to enhance architecture, fresco fuses paint and stone together and has been used since Ancient Roman times.

The mural remains on view in the Kentucky Museum's lobby. Learn more about the mural process and view the artists' talk here.

Learn more about Jonesville via the following:

- Jonesville History Project created by WKU Honors students Catherine Rice, Chelsea Murray, and Emily Peck (Fall 2014).

- Jonesville: An Neighborhood in Bowling Green, Kentucky from Gordon Van Ness on Vimeo.

- The Jonesville Controversy paper written by Ali Wright as part of a History & the Internet class in Spring 2004.

- Photographs and objects relating to Jonesville are in KenCat.

- Oral history interviews held by WKU Folklife Archives:

- Angela Townsend, a former resident of Jonesville, 2012.

- Records from the WKU Department of Library Special Collections include:

- Map of Jonesville land to be acquired by WKU, dated 1963. Other maps are available in TopScholar.

- A map of property owners, dated May 1963.

- Additional documents on the acquisition from President Kelly Thompson's correspondence.

- Dedication of the Historical Marker for Jonesville, including the program, 2001.

- Newspaper and other clippings regarding Jonesville.

- "Jonesville" by Maxine Ray, part of the Landmark Report Vol 18, no. 3, 1999.

- "Blacks in Bowling Green" project by Mella Jena Davis, 1990.

- Newspaper clippings regarding the urban renewal in Jonesville, 1962 to 1965.

- Map of Jonesville land to be acquired by WKU, dated 1963. Other maps are available in TopScholar.

This exhibit was conceived and created in large part through the efforts of the 2022 Community Scholars Program participants, the Kentucky Folklife Program, the Kentucky Museum, and the Department of Folk Studies and Anthropology at WKU.

Research, exhibit planning, and photo collection by the Spring 2022 class of Community Scholars: Wathetta Buford, John Conley, David Greer, Lamont Pearley, Maxine Ray, Alice Gatewood Waddell, and Alonzo Webb, with assistance from Kentucky Museum and Kentucky Folklife Program staff. Special thanks to Ali Wright (WKU class of 2006) and George "Tripp" Carpenter (WKU class of 2014) for their work, which provided historical context.

Exhibit narrative by Brent Bjorkman and Joel Chapman, with editorial assistance from Ann K. Ferrell. Layout and Design by Tiffany Isselhardt.

Oral History interviewees: Bobby Austin, James Bailey Jr., Wathetta Buford, Harold Hardin, Connie Gatewood Jones, Maxine Ray, Tremayne Taylor, Angela Townsend, and Alice Gatewood Waddell.

Images courtesy Maxine Ray, James Bailey Jr., Connie Gatewood Jones, and WKU Special Collections Library. Special thanks to Alice Gatewood Waddell for the use of images from the Jonesville buon fresco mural. Quotes by Maereeth K. Whitlow and C. L. White courtesy WKU Special Collections Library.

Kentucky African American Heritage Commission

Kentucky Arts Council

WKU President's Office and Jonesville Reconciliation Committee

with special thanks to

African American Museum of Bowling Green

WKU Potter College of Arts & Letters

WKU African American Studies Program

WKU Department of Folk Studies & Anthropology

WKU Department of History

WKU Special Collections Library