Cosmic Storm Chasers

The Universe is a dynamic place. Galaxies fly apart in the afterglow of the Big Bang. Planets dance around the Sun and other stars, which seethe with internal energy. And in deep space, new stars condense out of huge, churning gas clouds like raindrops in a summer storm. We can glimpse many of these phenomena with optical telescopes, but often radio waves, x-rays, or other types of electromagnetic radiation give a better view -- sometimes the only view -- of things that would otherwise remain hidden.

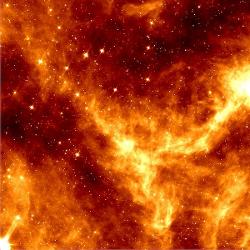

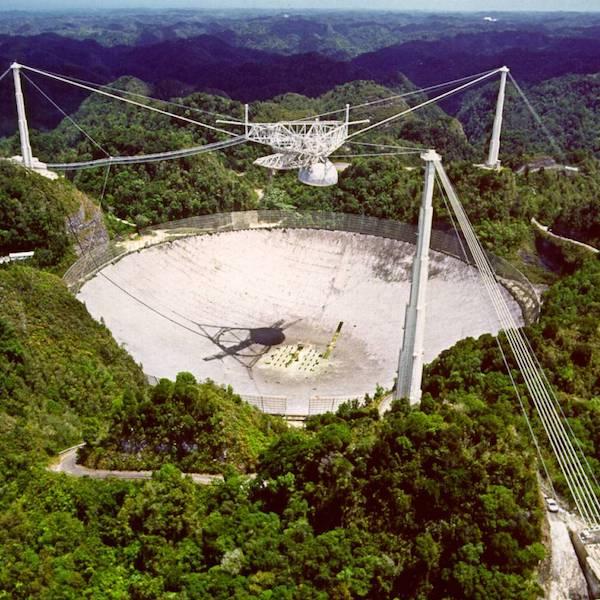

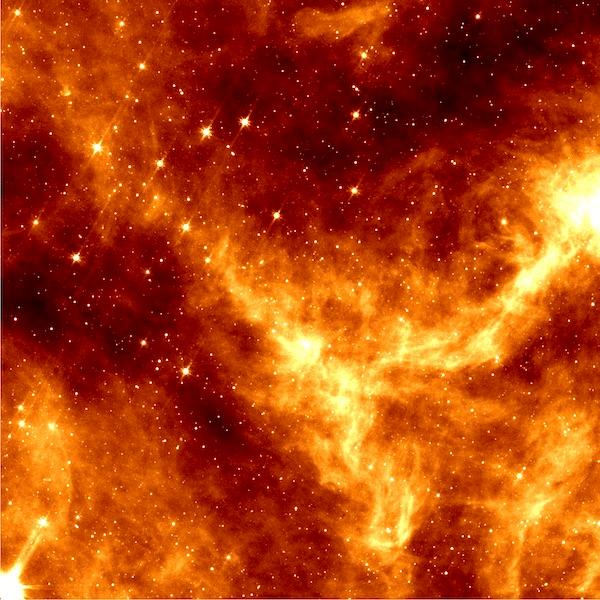

Our Galaxy, the Milky Way, is an enormous, rotating disk of billions of stars, only a small part of which is visible as a band of light stretching across the night sky; the rest is masked by the fog of dust particles that pervades interstellar space. But this fog becomes transparent at longer wavelengths. At WKU, Dr. Steven Gibson and his students are exploring the entire Galaxy using large radio telescopes around the world and infrared space telescopes in orbit. These tools allow them to see interstellar clouds slowly building up enough density to collapse and form new stars in the next few million years. Like terrestrial meteorologists, Gibson’s team is mapping these gathering "thunderheads" to learn how, where, and why they assemble, so that we can forecast star-forming "weather" across the Milky Way. Students involved in this research have won many conference awards, and several have pursued subsequent graduate work in astrophysics.

Closer to Earth, the planet Jupiter -- the largest in our Solar system -- traps charged particles from the Solar wind in its powerful magnetic field, where they mix with others thrown out of volcanoes on Jupiter's moon Io and trigger both optical aurorae and bursts of radio waves. The latter were monitored intensively by WKU astronomers in the 1960s and 1970s to tease out the intricate waltz of the planet's rotating magnetosphere. Today, we honor that tradition by giving our students hands-on field experience with radio equipment that tracks magnetic storms on Jupiter, as well as Solar flares that can stir up the Earth's own ionosphere and disrupt electronic communications.

A community of faculty, staff, and students engaged in better understanding the physical world.